| |

| Rabbi-to-be lost his faith in Shoah and became Lithuania’s top author | |

The 89-year-old’s novel, published in English for the first time, focuses on the tragic fate of the Jewish community in rural Mishkine, Lithuania, in 1941, from the point of view of multiple narrators. Kanovich’s works, translated into 14 languages, form an epic Litvak Saga — a memorial to a community now vanished. Kanovich, who has lived in Israel since 1993, was awarded the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Arts in 2014. Two years ago, Noir Press published his Shtetl Love Song, while the play Smile Upon Us, Lord, based on two of Kanovich’s novels, has been adapted by Rimas Tuminas and is being screened in cinemas across the UK this month. Kanovich — who has two sons, Dmitry and Sergey — was born in the Lithuanian town of Jonava on June 18, 1929. When the Second World War reached Lithuania, he fled with his family to Russia, via Latvia. After the war, he returned to his home country and studied at Vilnius University. He started his literary career in 1955 with Good Morning, a volume of verse. Five years later, he published Spring Thunder before writing for the stage and film. He has written more than 10 novels dealing with Jewish life in eastern Europe. Kanovich — who was declared a Citizen of Honour of Jonava in 2013 — told the Jewish Telegraph that the Holocaust “had a profound impact on my creative work”. He added: “Some members of my family perished in the Shoah. Both in Oswiecim (Auschwitz) and in the ghetto — my grandmother Rokha, who is the main protagonist in Shtetl Love Song, and my uncle Izik.” Lithuania’s Jewish population ballooned from around 160,000 before the Second World War to 250,000 in 1941. But after the Nazis invaded in June, 1941, almost 207,000 Jews were murdered. Kanovich’s family decided to return to Lithuania after the Holocaust. “It was not my decision; I did not even hold a passport at the time,” he said. But how were Jews treated in the country after the war? “I am not willing to jump to conclusions,” he replied. “Lithuanians acted in different ways: some accepted the Soviet rule, entered the Communist Party and took leading positions. “Others took to the woods. Those in leading positions had a loyal attitude towards the Jews. The Party leader, i.e. the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CP of Lithuania, even had a Jewish wife.” The Holocaust, though, ended Kanovich’s religious beliefs. He explained: “My grandmother wanted me to go to Telshiai after my primary school, enter a famous yeshiva there and become a rabbi after graduation. “The war, though, shuffled the cards. It drove the rabbi-to-be and his parents off to the step of Kazakhstan. That was the end of my religious pursuit.” He added: “It is immensely difficult to write about the Shoah, especially when the tragedy touched the author personally.” Finally, in 1993, Kanovich moved to Israel. For the four years before making aliya, he had been chairman of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. “There were very few of my readers left in Lithuania,” he told me. “At least, that was what I thought at the time. “So, I moved to where I had encouraged the Jews of the former USSR to move — to our home country, to Israel. “I lived in Kfar Saba for some time and later we moved to Bat Yam, a city next to Tel Aviv.” He used to visit Lithuania each year with his wife Olga “when we were healthy enough to travel”. At the moment he doesn’t see a long-term future for the Jewish community in Lithuania — which 14 years ago numbered 2,000. “They decline in number year by year,” he said. “I will be very happy if my prophecy does not come true.” Kanovich considers himself to be a Jewish writer — “however, I write my novels in Russian. I lost my native Yiddish after the end of the Second World War,” he explained. It’s almost four years now since Kanovich last wrote — one year older than his father was when he retired. He said: “My father was a tailor. He stopped sewing when he was nearly 85 and couldn’t thread a needle himself any more. “I put my pen aside when I was 86. I didn’t want either to repeat myself or write much worse than I had been writing before.” But he is delighted that British readers are now able to read his works. He explained: “My novels were translated and published in many European countries and in Israel. “In Britain, they have started publishing them very recently. The matter is that I have always been completely absorbed by my creative work and have never run after the publishers. “I have never hung on their coat-tails or begged them to publish my books. “I am happy that the publication of Shtetl Love Song in Britain is being followed by Devilspel.” Dr Paul Socken, professor emeritus of the University of Waterloo, said Shtetl Love Song and Devilspel “will no doubt constitute an important part of the literary canon of eastern European and world literature and stand as a lasting legacy that readers everywhere will reflect on for generations”. He added: “Kanovich’s work transcends Lithuania and represents a broader eastern European tragedy — the ugly truth that a people committed to its country, be it Hungary, Romania or Poland, were not considered true members of their society and were systematically murdered en masse when the opportunity arose.”

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|

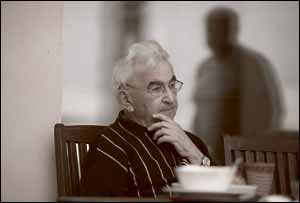

LITERARY CANON: Grigory Kanovich

LITERARY CANON: Grigory Kanovich