|

THE GREATEST EVER JEWISH FILMS Munich reverses paradigm of the Jew-as-victim | |

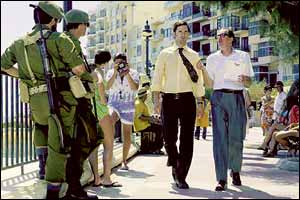

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir assigns a counter-assassination team, led by Avner Kaufman (Eric Bana), to kill the leaders of Black September, who were responsible for the atrocity. Bana is a non-Jewish hunk. As the only member of the team depicted naked, he is the fulfilment of the Zionist project of a 'Jewry of muscles'. He is virile and shown with his pregnant wife. The subsequent birth of their child proves his potency and ultimately Avner is presented as a good father who protects his family and his country. At least one reviewer described the team as handsome, scrupulous, exceptionally well-mannered Jewish agents. Munich reverses the traditional paradigm of the Jew-as-victim. Avner is the son of a Holocaust survivor, thus transforming the victimised into the victimiser. These Jews are, on the surface, assassins driven by bloodlust (Jews as Jaws perhaps), as well as vengeance. Jewish officials are shown to be zealous, chilly and clearly using the agents. The team kills in cold blood and sometimes takes cavalier, intemperate and undisciplined revenge. Steve (Daniel Craig), the South African driver, articulates these sentiments unambiguously: "Don't f*** with the Jews." For this last reason, Munich is celebrated in Seth Rogan comedy Knocked Up for its reversal of the typical cinematic Jew-as-victim stereotype. Ben: "Dude, every movie with Jews, we're the ones getting killed. Munich flips it on its ear. We cappin' m***********s." Their admiration for Munich, as a major ego boost to the contemporary Jew, says much about the changing cultural representations and cinematic stereotypes of Jews. Yet these agents are not monochromatically tough. With the exceptions of the non-Jewish Avner and Daniel Craig, announced to be the next James Bond while filming Munich, they are in the main presented as ordinary and normal. Unlike their superiors, they have moral qualms about their task, and as their collective mood depresses the film gets darker in both tone and lighting. They do not want to become like their enemies. With the exception of Steve, they struggle with the assignment, disagreeing with it, yet unable to refuse it at the same time. Ultimately, the team is ineffectual against the hydra-like rise of terror and, by the end of the film, Avner becomes an obsessive paranoid. Convinced that the Mossad wants him dead, he rejects Israel, abandons his homeland for America, permanently relocating his family to Brooklyn, suggesting that this part of the Diaspora is the safest haven for Jews. Thus, the film's theme is of the futility of meeting violence with violence. Spielberg designed the film as both an allegorical response to George Bush's 'War on Terror' as well as Israel's targeted assassination policy. It interrogates the efficacy, appropriateness, and ethics of state-sanctioned violence, revenge and counter-terrorist techniques at a time when these are much in evidence to ask whether they are successful or ultimately futile in their counter-productiveness.

|