|

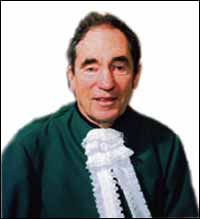

PROFILE Disfigured - but Albie bears no bitterness | |

THERE is no hint of anger or bitterness in Albie Sachs' voice. Perhaps that is somewhat surprising considering two spells in solitary confinement and exile - not to mention having his right arm blown off and losing his eye in a car-bomb attack.

And his alleged crime? Fighting the evil that was apartheid in South Africa. "I was fighting for freedom and was motivated by deep and humane ideas, yet we were labelled terrorists," he said. "That distorted the very nature of the struggle - the irony is that I was a victim of state terrorism." The "we" he is talking about is the African National Congress party, which Albie joined as a young man and played a prominent part in bringing about justice to South Africa. He eventually helped to create the new South African constitution following the collapse of apartheid and was appointed to the newly-established Constitutional Court by old friend - and party comrade - Nelson Mandela. A lawyer by profession, he also became one of the top judges in the land. Even a devastating car bomb, where he was close to losing his life, didn't stop Albie's determination to rid South African of its horrific racism and segregation of its black majority. His story is told in the latest update of his award-winning book The Soft Vengeance Of A Freedom Fighter. Many Jews such as Albie were vociferous in their anti-apartheid fight, including Joe Slovo, Helen Suzman and Ruth First. The ANC established underground headquarters at the farm home of Arthur Goldreich in Johannesburg. Mandela stayed there in the guise of a farm worker and it was there that a military arm, The Spear of the Nation, was conceived. "Jews in South Africa grew up with a lot of idealism in our hearts, as well as with a sense of justice," Albie said. The majority of South African Jews are sons and grandsons of those who fled pogroms. "I grew up with the stories of the pogroms," Johannesburg-born Albie recalled. "We didn't slot into Afrikaner society, into an obvious place and a lot of Jews who came to South Africa did so with socialist ideals." Brought up in Cape Town by Ray and Solly, Albert Louis Sachs was aware of apartheid from a young age. His mother was a typist to Moses Kotane, the secretary general of the South African Communist Party. "Mum had so much respect for him," Albie recalled. "I was taught to show respect for everybody - it was something natural for me. His anti-apartheid activism started when he was a second-year law student at Cape Town University. Taking part in the Defiance of Unjust Laws campaigns, Albie was there when the Freedom Charter, which was later to form part of the 1994 new constitution, was adopted by the ANC and other anti-racist groups. It was during this time that he first met Mandela. Albie remembered: "He and Oliver Tambo ran a law practice and I would go to Johannesburg and have a cup of tea with them. "As a lawyer, I was defending people who were victims of apartheid." But Albie's work attracted unwanted attention from the South African government. Arrested, he spent 168 days in solitary confinement. "Beyond the isolation, they tortured with me with sleep depravation," he recalled. My interrogators would bang the tables incessantly for 20 minutes, making lots of noise, be quite for three minutes, then carry on. "They would do it at all times of day and night - my fatigue became greater and greater. "One time, they gave me something to eat and they smirked as I ate it. Suddenly I had an intense desire to sleep and then I broke down completely, collapsing on the floor. "They poured water on me when that happened." Albie said his mother was extremely concerned about him, but that she was proud. "I was taking on a vicious and repressive state system," he continued. Sent into exile, he went to England where he met and married first wife Stephanie Kemp, a fellow anti-apartheid activist. He taught law at Southampton University, before becoming a professor of law in the African country of Mozambique. The ANC were extremely active in Mozambique, which bordered South Africa. Making his home in Mozambique, Albie settled in the capital Maputo. "We ANC people had to be careful because South African agents would kill our members near the border," he explained. Fellow activist Ruth First had been killed in 1982 by a parcel bomb. But however much caution Albie took, his life change on April 7, 1988. A bomb was placed in his car by South African security agents. "It was a public holiday," Albie said. "Suddenly there was a terrible darkness and I knew something bad was happening." He woke up in a hospital bed in Maputo hospital to be told bad news by close friend - and doctor - Ivo Garrido. "I felt very light and weird, so I told myself a Jewish joke to try to cheer myself up," Albie recalled. "I wasn't - and I am not - religious, but it was not an accident that I told myself a Jewish joke the moment I nearly lost of my life. "I used humour to deal with disaster and that is a very Jewish thing to do, but I had to face the future. "Jacob Zuma (current South African president) came to see me and he tried to cheer me up with black folk stories and jokes. "That pleased me because I combined Jewish and black humour and saw that we all would have a place in the new South Africa. "Eventually, as I got better, my country got better." Because of the loss of one of his arms, as well as an eye, Albie had to learn to stand, walk, run, tie a shoelace with his left arm and learn to write with his left hand. "There was a feeling of immense liberation," he said. "It was like being a little boy again and learning how to do all these basic things. I felt like saying, 'Look mummy, I can tie my shoelaces'." Albie returned to South Africa in 1990 after Mandela had been released from prison. The country was changing and Mandela would soon be elected president. "It was fantastic - an absolute joy," Albie said. "We were back and on the road to democracy." Albie served as a member of the Constitutional Committee and was appointed by Mandela to the ANC's national executive. "The more time Mandela spent on Robben Island, the more powerful figure he became, a symbol," he explained. "I met him after he was released from prison and we embraced." More than 10 years after the car bombing, Albie came face-to-face with the agent who planted the bomb. The country's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, assembled after the abolition of apartheid, had put many of the previous governments' ministers and agents in the dock. "I had a phone call to say he was at my office at the constitutional court," Albie recalled. "He asked if I was willing to speak to him and I was - my heart was beating quite fast when he came in. "We had a discussion, but when we said goodbye, I just couldn't shake his hand. I told him to go to the Truth Commission and tell them what he knew." The Soft Vengeance Of A Freedom Fighter is published by Souvenir Press, £15.

|