|

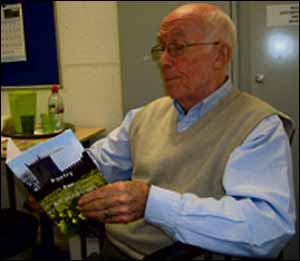

PROFILE Surgeon Martin turns his hands to poetry | |

THERE'S a touch of the poet about retired orthop-aedic surgeon and sculptor Martin Andrew Nelson.

With more than 200 poems under his belt and a small book called Poetry For All Occasions published in Mombasa, Martin is well on his way to fulfilling his dream of becoming a creative writer. "I'm used to the genre. As a doctor one is always writing and much of that is professional - about patients, case-histories and research," he told me on a whistle-stop visit to Leeds. Currently spending time in Kenya as well as in this country, Martin said it was natural for him to put pen to paper, but confides that creative writing is a very strange animal indeed. It's a different form of writing than almost any other, he explains. "The subject provides you with the background to all sorts including novel writing, short-stories and children's literature. And one of these was poetry, which I found highly engaging." Martin, articulate, sensitive and with an easy-going charm, was attracted to the immediacy of poetry and the way he could get an idea and develop it rather quickly and succinctly. "It has a flow and a musicality which appeals enormously to me." He's a poet who tends to edit a great deal, usually up to nine times, to try to find the right word, possibly because it doesn't scan properly or the rhythm has been lost. "My work is structured so I suppose this method is in keeping with my profession of being an orthopaedic surgeon - I like moving things around and chopping things up," he quips. Martin is inspired to write by mere observation and once he has the first line, away he goes. "Recently, I was on a bus going to the British Library and stopping in Euston I saw a war memorial and read the inscription of how we should glorify the dead -Dulce Et Decorum Est . . . how sweet and honourable it is to die for one's country. "I felt really angry about how we read these words not realising the pain and suffering of what those young people went through; the futility of war and the waste of young lives. So I wrote a poem about how I felt." The way Martin constructs a poem is all important. Take bananas for instance. "I wrote down everything I could think of about bananas, their colour, how they are grown, the texture of the fruit and how they feel in the mouth, and who eats them and where they come from. Then I shifted all the information around. The result was Yes, I Love Bananas." Is he a stickler for rhyming couplets? Not at all, he says, although he's meticulous about inner-rhymes. So, not often following the accepted rules of composition, he's happy to call his work 'free verse' which has a long history back to Shakespeare. In Kenya, Martin is part of a small poetry reading group which meets monthly and consists of local people as well as Europeans. "It's a lovely group. I was thinking of setting up a workshop for them, but they don't want criticism, they just want to enjoy the pleasure that poetry often generates." He also taught in schools where he gave a 90-minute talk on poetry and had a wonderful response from the children who were 11-12 year-olds. "Love was a big subject with them: boy-loves-girl and unrequited love, that sort of thing. It was lovely really, very refreshing," he said. "Also the kids in Kenya write about animals; remember we are in Africa where we are very close to wildlife, so everyone is aware of nature. It's a very inspirational landscape." Martin was born in Hackney, London, in 1932. After war broke out, the family moved to north London. Then his father thought they would not survive and so his mother, Martin and two brothers were evacuated to Bermuda. They returned to London in 1945 and, after his parents divorced, Martin was sent to a public school in Mill Hill. "It was there that I met a very inspired teacher in the sixth-form and it was he who suggested I do medicine," he recalled. "My parents, neither of whom had an education beyond 16, knew nothing about university. "In fact, I think I was the first in my family to have a higher education. After university I got a small scholarship to St Mary's Hospital." Martin was a senior registrar at Guys Hospital when, looking for a consultant post, a position came up in Leeds. He was overseas at the time when he received a communication from his wife Diana. Martin had previously prepared an application for a placement in Leeds and Diana asked if she should mail it. He was uncertain, but reluctantly agreed, the furthest north he'd been was Sheffield. "So Diana posted the application and that was the job I eventually got. It was a wonderful decision," he said. It was in 1968 on a visit to Baltimore that Martin met the Little People of America, the organisation for people of short stature. On his return to England he was influential in setting up a steering committee that formed the Association For Research Into Restricted Growth, now known as RGA, a self-help organisation. Martin feels fortunate because he's been given hands that are very useful. He can do exceptional things with them, so was it natural that he would gravitate towards surgery? "Yes, it looks that way. I did a job in orthopaedics and was fascinated with the way bones can be put together so I became an orthopaedic surgeon," he said. "It was very natural to use hammers, chisels and drills, and this, of course, was to prove useful later on in life when I turned to sculpture." After completing his MA in sculpture at Bretton Hall, he joined the Yorkshire Sculptors Group and has exhibited alone and in group shows which include The Henry Moore Institute Library in Leeds and Rotherham Art Gallery. Martin's stone carving and wood engraving explores the intrinsic qualities of his chosen materials, he particularly likes serpentine, a workable stone found in abundance in Zimbabwe. The difference between surgery and sculpture, Martin says, is that stones don't bleed but they are much less forgiving. "If you make a mistake with bones, they will heal - the same can't be said for stone'. The death of his artist wife Diana, whom he first met when she was 16, had a profound effect on Martin in terms of the solemnity of it all. There are a series of poems written shortly after her demise that are particularly poignant. The Day That Changed My Life is a moving example and one wonders if he found putting his thoughts down on paper cathartic. "Yes, that helped enormously. In many ways writing is like having a dialogue with oneself - it's an amazingly comforting form of activity," he said. Martin has also written 15 short-stories which he hopes to bring out in a book. The stories also happen by chance, he says. On one occasion he was walking along the street and saw a left-footed sandal. His imagination sprang into action, how did that sandal get there, was a little boy running away from something, maybe he didn't want to be late for school and so on? Before he knew it, the story had a beginning, middle and an end. "Diana was a highly talented artist and I used to go with her to a number of exhibitions," he said. "I also went to night-school and was able to benefit from doing some drawing and sculpting while I was still working here in Leeds. "This allowed me to put together a portfolio so when I retired I went to Sheffield where I did a five-year course for a BA for Fine Art for people with unusual CVs." He said: "I don't know where all my creativity comes from, but I suppose we all have that gift of inventiveness - we just need something to trigger it off."

|