|

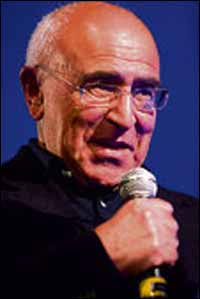

PROFILE Filmmaker Edward's right royal legacy | |

MAKING pioneering television was not a burning childhood ambition for Edward Mirzoeff.

But through a series of fortuitous incidents, his name became synonymous with groundbreaking documentaries. His filmmaking career spanned five decades and often he opened the opaque doors of some of Britain's elite establishments - the monarchy, the Ritz Hotel, and the armed forces - to the nation's prying eyes. Despite admitting that he "never had a professional purpose", he acted as a tour guide for millions with his landmark films Bird's Eye View, The Regiment and Elizabeth R. And at 76 years of age, Edward remains one of the most venerated figures in British TV history. A Londoner born and bred, he did not grow up in a "creative household". His parents were from Uzbekistan, where his father was a "businessman in the fur trade while there was still such a thing". The family absconded around the time the Soviet Union usurped the Uzbek government. They reached Palestine, before moving on to England. Edward, a four-time BAFTA winner, explained: "They were traditionally Jewish in their beliefs. "It was a standard that they kept the festivals and went to synagogue. I was sent to school in the early days of Hasmonean in London. It was a pretty shambolic place then. "In a way it was understandable. It was newly founded, some of the teachers were qualified and some were not so it was variable in its educational standards. "But it was very much the Orthodox Jewish school. The religious element was strong - observances and customs were part of the deal. It affected me the other way quite strongly. "I didn't believe a word of it. I didn't like it. I found it very alienating." A career in TV was never a consideration during his education. "Filmmaking was Hollywood or at best Ealing studios," he explained. "I fell into that later." Edward finished school and went off to Queen's College, Oxford, to study history from 1953-56, after which he "hung around" doing research for another two years. He navigated a series of "small, deadend job in the trendy areas of the time", until finally he chanced on the nascent market research industry. The former BAFTA chairman recalled: "I worked at a little mag called Shopper's Guide and the BBC felt that it ought to reflect this new consumer movement. "They couldn't because of the terms of the charter on brand names and commercial discrimination. So they would review the reports in a show called Choice, presented by Richard Dimbleby. "It was considered extremely daring and the lawyers were convinced the industry would sue. "By devious means, I managed to persuade them to make me the Shopper's Guide representative to the BBC. "I thought it must be more fun than analysing tests on ladies' cardigans. "It was the most adrenaline-filled world I'd ever encountered. I went home on a complete high." The magazine was disastrously purchased by Michael Heseltine, who went on to become the deputy prime minister, and Clive Labovitch. They modernised the graphics, but the readership mutinied. "The housewives in the Home Counties were totally bewildered by what was happening," Edward explained. A sense of foreboding descended on him and he began to proclaim that the project would "end in tears". He was summoned to Heseltine's office and told to leave. Luckily, he had built a vast contact book and headed over to the BBC to offer his services. "I said that I could offer my consumer talent to them, even though I had none," he recalled. "The woman interviewing asked me, 'Do you have any visual sense?' and I said, 'I definitely have it'. So they offered me a job. "Gradually, I started doing other things, from studio work to little bits of film." Edward's first major foray into filmmaking came through Bird's-Eye View - a pioneering series of films documenting for the first time the British Isles from the skies. It was not simply a set of films that spearheaded documentary making for British television, Edward had finally found his niche. He explained: "My whole career came off that. "It was a groundbreaking film. Every one of us knew it. "One of our more extravagant bosses, Aubrey Singer, used to think big and one of his big ideas was the BBC hiring a helicopter for three years. "He assumed it would pay for itself by all the departments using it. But it emerged that nobody wanted to use it. "It was jolly expensive and the BBC was stuck with the contract so they came up with the idea of making a documentary series using a helicopter. "I, a very junior person, had made one complete film and was told I was to be in charge. "It was the most expensive thing the BBC had ever made. They said to me, 'It's up to you, chum - go make 13 episodes'." Nobody in television had made anything resembling what Edward had been tasked with. But, he explained, "the wonderful thing about being groundbreaking is that you don't know what the problems are". Edward continued to conceive, produce and direct trailblazing works of television such as The Regiment, which observed the Royal Greenjackets, and The Yard, which laid bare the mystical halls of Scotland Yard. His proudest hour though came with Elizabeth R - a 1992 film that brought the Queen into the nation's living rooms in a manner not witnessed before. Famously, the Queen described the year as her annus horribilis. In the context of divorces, royal scandal and a devastating fire at Windsor Castle, Edward was told his film was the "only good thing" to happen to the Queen that year. He recalled: "It had a phenomenal audience. Thirty million watched it. I was trying to show what the Queen was really like. "The brief I had was slightly different. They wanted to show the constitutional role of the monarchy. "But it's as dry as dust and it wouldn't have made much of a film. I decided to do something that was more interesting and looked at more of the person. "At a time when the Queen was rather disregarded, there was a need to remind the nation what she was like." Two decades later, he still looks back wistfully. "The memory of the film still lingers," Edward said. "It was the most amazing experience of being able to film for a period of 18 months. I used to think 'golly, what am I doing here?' "There were lots of moments when I kept thinking 'How did I get here? What am I doing sitting as the only outsider in a conversation between the Queen, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the American president?' "It was truly fly-on-the-wall because you couldn't ask for people to do something again." But his work was not exclusive to British subjects. Edward also made films such as Israel: A Promised Land, which celebrated the Jewish state's 30th birthday and was fronted by veteran reporter James Cameron. He recalled: "The first complete film I made was on Jerusalem in 1967, immediately after the Six Day War. "Journalist Malcolm Muggeridge had been sent to Israel to make films on the life of Jesus for the religious department. "While he was there he got in touch with former prime minister David Ben Gurion and talked him into an interview. "He got in touch with London and asked for a producer. "They looked around at who wasn't doing anything and they asked me to hold his hand. "I was going all that way so I asked if I could make a film and they agreed." A reunified Jerusalem was too good an opportunity to miss. "When I did Jerusalem the Golden I was trying to be objective, being conscious of being Jewish," Edward said. "But David Attenborough told me that he wished I had been a bit more emotional and pinned my stripes to something." The modern television era has seen "reality gallop in," he lamented. "It's cheap and effective programme making. I can see why commissioners are keen on it. But it's sad that you can find documentary only on odd corners of BBC FOUR late at night. "We are now working with people who are brought up in telly. They haven't had the roughness of living in somewhere else and learning in a different way. "It doesn't have the same breadth and authority." Two of Edward's three sons are making tracks in the industry. Daniel works for the BBC and Sacha, a documentary maker, has been nominated for a BAFTA for his series Protecting Our Children. Edward and his wife Judith have another son, Nicholas, and five grandchildren. Since retiring from filmmaking, he became a chairman and is now patron of the documentary filmmaking charity the Grierson Trust. He said: "I get involved in occasional projects when I'm asked to be executive producer. "I write articles, go on holidays and read books. Once you're in TV you never get beyond it."

|