|

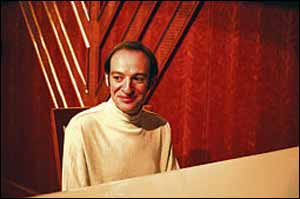

PROFILE Sweet music as Alexander keeps Jewish traditions alive | |

THE life of Moscow Male Jewish Choir conductor Dr Alexander Tsaliuk epitomises Russian Jewish history over the last century.

His maternal grandfather Leibl Rayak was born into a rabbinic family in Belarus in 1907 and shared a cheder desk with chassidic painter Marc Chagall. To escape the pogroms, Leibl's family fled to Moscow, where they joined the capital's Grand Choral Synagogue in 1914. Leibl became the ba'al tefillah (prayer leader) of the congregation right through the Communist era, despite the regime's crackdown on the practice of Judaism. Recalling his grandfather, who died at the ripe old age of 96, Alexander said: "He never stopped going to the synagogue since 1914, even during the Stalinist repression when it was very difficult and dangerous. "He was the ba'al tefillah in the small hall of the Moscow Grand Choral Synagogue. He was very religious because both his grandparents were rabbis in Belarus and always kept Shabbat and yomtov. "He had siddurim and a Hebrew dictionary from the 1870s. I have a picture of my rabbinic great grandfather." Alexander continued: "When I was a child I went with my mother to meet my grandfather at the end of service. "It was the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s. The synagogue then was a place where Jews could meet and discuss their Jewish identity. "The people understood nothing religious, but the synagogue was a big club. "When my grandfather, who lived far from the synagogue, was almost blind I helped him home." When Alexander was born, Leibl wanted his grandson to have a brit. But his paternal grandmother went hysterical at the thought. Alexander told me the reason: "My paternal grandfather Shaya Tsaliuk was a soldier in the Soviet army in World War Two. "A professional photographer, he was going to German-occupied territory to investigate for the Soviets. "His plane was shot down. He jumped down with his parachute. "He and his pilot were taken by the German SS to prison. They were asked if they were Jewish, which they denied. "But the Germans told Shaya to take down his trousers. When they discovered from his brit that my grandfather was Jewish they immediately killed him. "But the pilot escaped. After the war he found my grandmother and told her how her husband died. "When I was born, she went hysterical at the idea of a brit. She said, 'Never do that to my grandson'." The story was made even more tragic by the fact that Bella Tsaliuk's husband was killed on the exact date of her birthday. Alexander said: "My babushka was an opera singer. When my father was a few months old in 1941, she fled with him from the Nazis from Ukraine to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. "She went to the local market to buy fruits for my father to celebrate her birthday. A blind guy was playing an accordion. "He played a Ukrainian song for her because she came from Ukraine. She started to sing because she had a wonderful voice. All the people surrounded them. "Then he told her, 'You are a very beautiful girl, but you are unfortunate because today is your birthday and today your husband died at the front'. She started crying and rushed home. "Two weeks later, she received a letter that her husband had died as a hero on August 24, her birthday. She became grey overnight and vowed never to remarry, but dedicated her life to my father." Gifted musician Alexander started studying music at the age of four and was a member of the prestigious USSR radio Big Children's Choir. He was a student at the prestigious Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory - one of the best musical colleges in the world - when in 1989 top American chazan Joseph Malovany persuaded Russian premier Mikhail Gorbachev to allow cantorial and choral music back into Russian synagogues in line with the policy of glasnost. Alexander recalled: "When Cantor Malovany visited Moscow for the first time in 1989, giving two huge concerts with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, he insisted he wanted to establish a male choir in the best of Jewish and Russian traditions. "My grandfather told the rabbi, 'My grandson could help you'. I was an 18-year-old student. He brought me to the synagogue and introduced me to his community members. "They were not musicians, but Yiddish neshomas. They sang like their grandparents. I started working with them, trying to learn songs like Roshinkes mit Mandlen and Shalom Aleichem." He continued: "Chazan Malovany sent me packages of liturgical material for synagogue and concerts, giving me lessons through the phone and fax machine while I was sitting at an old tape recorder, recording from the speakerphone. Malovany also kept coming to Moscow. "Eventually, we got finance from the American Joint Distribution Fund and employed other students from the conservatory as conductors and vocalists, Jewish and non-Jewish" "Malovany's idea was to attract people back to the synagogue with music of the highest standard. "If the Jewish intelligentsia went every night to hear Rachmaninov and Mozart, why could they not go to the synagogue and hear a fantastic performance of Jewish liturgy? "It was a fantastic idea to hook educated Jewish people who went to the Pushkin Museum and the Bolshoi Ballet. "There was competition to sing in the choir because Russian musicians love Jewish music." But this cultural revival of Moscow's Grand Choral Synagogue was brought to an end, not this time by Communism but by Jewish politics. Russia's main synagogue was taken over by its chief rabbi Berl Lazar, a Lubavitcher who disapproved of choral music, and the choir was ousted from its synagogal home and was left only with its concert audiences. Although simultaneously deprived of Joint funding, the choir continued, gaining an international reputation as one of the best Jewish choirs in the world. Desperate for funding, Alexander had to subsidise his own income through teaching and conducting another choir. But he is still determined to raise funds in order to engage "the best musical specialists to raise the level of Jewish music, to take the choir, which is in demand all over the world, out of the synagogue walls on to the international world stage, as high as possible like the Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Centre. "It is the Jewish equivalent of the Red Army Choir", he said. So what was Jewish life like now in Moscow? Alexander replied: "Superficially, it is very active and free, but spiritually it's a make-believe. "People go to the synagogue as a club, to get free services like welfare, lessons and medical help. "There are yeshivot, but it's very rare that Jewish kids go of their free will. They bring kids from the Caucasus where there is almost a war. "Moscow Jewish parents want to assimilate. They are still worried there might be a return to the old times. They hope that if Russia becomes a dictatorship they will not be accused of being too Jewish." But Alexander is determined that at least Russian Jewish musical traditions will survive whatever befalls his country.

|