|

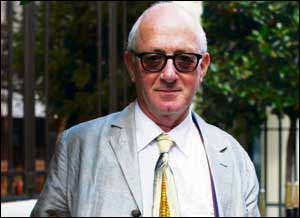

PROFILE Restaurateur-turned-critic Nick reveals the secrets of the trade | |

THE years have treated Nicholas Lander well - despite everything.

He looks trim and healthy and I remark on the fact that despite my love of food and wine and that he is a restaurant critic who eats out at least twice a week, with a famous wine writer wife with whom he samples countless wines at home, he has fared rather better in the paunch vicinity than I have. His formula, sadly, is not to have adhered to some new fangled diet, nor merely to eat with restraint. Nick's slim physique is at least due partially to a debilitating stomach condition from which he has suffered since schooldays and which might have cost him his life earlier this year. In 1968, while still at Manchester Grammar School, he spent a week in Salford Royal Hospital with an initial bout of ulcerative colitis, the condition which would dog him for the next 44 years. And on March 14 last year - the date is obviously etched in Nick's memory as it rolls off his tongue - the colitis flared up and resulted in an ileostomy, which means Nick must permanently wear a pouch to collect intestinal waste. That is never a minor procedure, let alone for the man who has been the restaurant critic of the Financial Times since 1989. As if that were not bad enough, he suffered atrial fibrillation, a heart condition, the day after surgery and because "I was not getting better", spent nearly a month in hospital, being released the day before his 60th birthday. Despite everything, he remains upbeat, still the cheery person I recall from our schooldays at Manchester Grammar. And he has just written a remarkable tome, The Art of the Restaurateur (Phaidon Press, £24.95) It tells the stories entertainingly behind some of the world's top restaurants. I probably like him more 45 years since we last set eyes on each other, since in our youth we also vied for the goalkeeper's jersey in the West Didsbury football team that competed in the Manchester Jewish Soccer League under-16s division. And it was Nick who was invariably selected to to stand between the sticks. He's probably rather more qualified to critique restaurants than most if not all of his fellow critics, having himself become an "accidental restaurateur". He is fiercely critical, incidentally, of his colleagues in the Press, none of whom contacted him when he was so seriously ill earlier this year. On the other hand, he heard from many of his wife Jancis Robinson's fellow wine writers, although in defence of the restaurant critics, he points out that they are fiercely competitive whereas the wine writers tend to "hunt in packs". But I digress . . . After reading history at Cambridge, he returned to his home city to study at Manchester Business School in preparation for entering his father Lennard's textile business, which he himself had taken over from his father-in-law, Willie Shalit, a stalwart of the local Jewish community. "Then I got a little bored," recalls Nick, "and went to Hong Kong to get it out of my system." He found employment there with a commodity trader and returned to London for six months for further training. But his father suffered the first of several minor strokes and that meant Nick's assistance was called for. Textiles were not for Nick though and he began importing wine from California. He soon realised there wasn't much money to made from the wine trade, but it did fund his purchase of what was to become the iconic L'Escargot restaurant in London and he became an "accidental restaurateur". The original intention was to expand the existing wine bar. "Suddenly," recalled Nick, "I found out what I had taken on. It only had a restaurant licence and I was saddled with a restaurant. "I had to make the most of it and happily it worked." Illness forced him to sell out in 1988, "before the crash", he points out, while they were serving 400 diners a day. But he had no choice. His wife Jancis said his face was at times "the colour of the green walls". He added: "I didn't really let it get me down and I was in love with my job. "I was very ill in 1985 and of course you don't really know how bad it is because you're out of it." He admits that he misses running a restaurant of that type but feels that he has "half a foot in the business by writing about it and doing consultancy work" and is extremely well-placed, as a former restaurateur, to comment on the business. But it was only a chance encounter in 1989 with the Weekend editor of the Financial Times that led to Nick's new career; he submitted a restaurant review on spec which he liked and the rest is history. Today it is difficult for him to remain anonymous as a reviewer. He's too well known and wearing his trademark red socks probably doesn't help. But he does not believe that in any way compromises his integrity, nor the fact that many of those who run the restaurants he assesses actually trained under him at L'Escargot. Even being aware of who he is, says Nick: "I'm still not sure what a restaurateur or chef can do to try and impress a critic - an extra piece of meat? - and the staff tend to get very nervous and something can go terribly wrong. Usually, one visit will suffice, but he has been known to eat more than once at an establishment. This, he admits, is something of a professional dichotomy. "Do you go to a restaurant several times and try lots of dishes, or do you behave like a customer does; go once and if you don't like it, don't go back?" Nick readily quotes New York restaurateur Joe Bastianich who features in his book. "During my second interview with him, he said that the restaurateur's biggest enemy is not the reviewer. It's his ego," recalled Nick."I think, in a way, that should be emblazoned above every restaurant." He believes that chefs have become obsessed with their egos and become bigger than their restaurants in some cases. Celebrity chefs were a bit like sportsmen, starting when they were 18, because they weren't very good academically, serving a tough apprenticeship and then suddenly becoming very well known like Wayne Rooney. "Who has taught them how to behave? The answer is nobody," observes Nick. "So why should we expect them to behave any better than they have done?" "The great thing about restaurateurs is that because they are out there facing their public they are far more sociable animals." In at least one respect he has sympathy for waiting staff. "If I've got one bit of advice for customers," Nick counsels, "it's to tell the waiting staff what they want. "Waiting staff are not mind readers. I think it's possibly a fault inherent in the English - we're a little bit too sharp and brash." But is the customer always right - whatever? "No," insists Nick, obviously reverting to his restaurant owner's persona, "but it's the restaurateur's job to make them feel when they leave that they're always right, and turning their potentially ludicrous request into something sensible." "If a customer wants a table on the roof, you don't say 'no', you say, 'Hang on, I will just go and see if that is possible' and you come back and say, 'Actually we're not serving up there today'. "It's just a question of how you rephrase it all." But before booking a restaurant, the prospective patron should research it to check that it appears to be giving good value for money. "Listen to other people's opinions," he adds, "but probably take everything with a pinch of salt, including the restaurant correspondent of the Financial Times. "A friend's opinion is possibly worth more than an average from one of the guides, where the good are excluded just as the bad are and you end up with the medium." Nick was barmitzvah at South Manchester Synagogue and in his new book pays tribute to his mother Pauline's cooking. "She used to spend a day organising what was going to be eaten," he recalled. His father was one of nine children born to David and Rachel Lander, who were stalwart members of Liverpool's Princes Road Synagogue. Nick says his Judaism has always been important to him - particularly the food aspect. "Certainly. the sense of welcoming friends, family and strangers into your house, feeding them, looking after them and making them welcome, which is endemic in Judaism, is something that I think has been absolutely invaluable to me," he says. "And I think it's what distinguishes the restaurateurs in my book as well. Jews, Italians and Irish all have that sense of welcome." He adds: "There are tenets of Judaism that are still very close, like looking after fellow human beings and treating people as you would like to be treated." What type of restaurant does he favour as a paying guest? Because his wife is a wine writer, it must have a good wine list and because he's a northerner, he says, it must represent good value. And because he knows the price of most food, he does not want to be confronted by a menu that looks overly expensive. "I want to be made to feel welcome and I think that's increasingly common. I don't want to be processed, which is what a lot of the big restaurants are becoming. He sees cover charges as "outrageous" and is meticulous about checking his bill. Why did he write the book? "It's been building inside me. I feel restaurateurs have been ignored for far too long. "I sensed -and I hope I'm right - that the pendulum is shifting back to the sense of welcome and people being cared for rather than being challenged by food. "And I felt absolutely fascinated by a lot of these people's stories which I didn't really know. I knew them, but I didn't really know them well. The interviews taught me about them as I hope the book will inform the readers. The book, he says, is aimed at anyone who loves going to restaurants or intends entering restaurant management. I conclude our interview by pushing Nick on his personal recommendations for eating out. "It's hard to dissociate work from pleasure," he observes, but nevertheless declares: "The perennial has always been St John in Smithfield, not just because of the food that I had on my 50th birthday party but because of the memories." He names The Sportsman at Seasalter in Whistable, Le Gavroche, Racine, in Knightsbridge, Chez Bruce in Wandsworth and the restaurant at the Goring Hotel where the former Kate Middleton and her family stayed before her marriage to Prince William. So now you have it . . . straight from the horse's mouth.

|