|

PROFILE Henry damned happy to take the role of man who fired legend Brian Clough | |

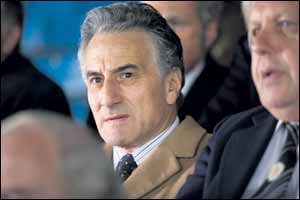

The 59-year-old's latest film role was as Leeds United's Jewish chairman Manny Cussins in the critically acclaimed The Damned United - based on the life of legendary football manager Brian Clough. But among his many other roles have been Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, as well as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice - for which he won the prestigious Olivier Award. Henry said: "I am not an ambassador for Judaism, but I do have a great love for the festivals. "I cherish and respect the traditions." His journey to film has been an eclectic one. From street theatre at the 1972 Munich Olympics to fighting apartheid in South Africa through drama, he has had a varied and exciting career. Born in Whitechapel in the heart of London's East End in 1950, of Lithuanian and Polish Jewish descent, he recalled that his parents wanted the family to be as integrated as possible. Henry remembered: "My parents wanted to be English and so gave their children English names. "We lived in a tough and dangerous neighbourhood with a whole mix of people - Irish, black - but we had to get on with one another. "My brother still lives in the East End and, although now it is predominantly Bangladeshi and Somali, he has had no problems." The acting bug bit Henry when he was just 10 years old. He was cast as a child in the film Conspiracy of Hearts, which also starred Sylvia Syms and Jewish actor David Kossoff. It told the story of wartime Italian nuns who regularly smuggle Jewish children out of an internment camp near a convent. Henry explained: "I used to get driven in a Rolls-Royce to Pinewood Studios every day. "It was fantastic and I got time off from school, too." Before directing his first musical at a local youth club when he was 16, Henry attended Toynbee Hall, an arts centre off Petticoat Lane in the East End. "It is rather chic now, but it was rat-infested then," he recalled. He later secured a place at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, in London, in 1969. "People may think that those who went there were from privileged families, but RADA went out of its way to ensure there were people there from a range of social backgrounds," Henry explained. After graduating, he headed to the now-infamous 1972 Munich Olympics, where he took part in street theatre at the competition's Spielstrasse. The Olympics became known for the murder of 11 Israeli athletes, killed in cold blood by Arab terrorists. Henry recalled: "The village where the hostages were held was not close, but it was in earshot. "It was scary and the thought did cross my mind that there would be some terrorist creeping around the bushes looking for more Jews to shoot." But there were some pleasant moments at the games, such as when he took part in the reopening of the games. He said: "The people who took part in the street theatre were from all over the world. "It was about dissent and arguments, but that was what theatre back then was about." Henry met his wife, dance-teacher Sue Parker, while in Switzerland and they later moved to South Africa in 1973. And it was not an easy time for him in the apartheid state, where he and Sue lived in Cape Town. Henry continued: "I put on plays against racism - we mixed black and white actors together. "I am not a political radical. It was just an act of pure decency. "I had to go to the police courts a number of times to justify why I had put black actors on the stage." The couple left South Africa in 1981 as Henry wanted to get his teeth stuck into Shakespeare. He auditioned successfully for the Royal Shakespeare Company and has been working on a regular basis on stage and screen since the 1980s. And his talents have been recognised by his peers, picking up the Laurence Olivier Theatre Award in 1993 for his role in Musical for Assassins and collecting another one seven years later for Shylock in The Merchant of Venice at the Royal National Theatre. Henry said: "A lot of actors dismiss awards. "I am not in this industry to pick up awards, although they are always pleasant. "It is, however, important to keep it in perspective." He sees acting as an ongoing battle and insists that actors are creative creatures. He added: "It is important creatively to have dialogue with yourself. "Many people are of the opinion that actors are parasites who just interpret other people's work. "But we are not - we are creative spirits." He admits that he does not know much about football, nor about Leeds' chairman Manny Cussins - the man who fired manager Brian Clough after just 44 days in charge, who he played in The Damned United. Recalling the hooligan days of the 1970s, he said: "It was not pleasant and it was not my world. "I did read David Peace's book on which the film is based. "The director Tom Hooper did cut a few of my scenes, but I was not too perturbed - the film was really good as it was." His career has not all been plain-sailing, though. Controversy arose in 2002 after Henry was cast as Max Bialystock in the Broadway production of The Producers, taking over from Nathan Lane. However, his interpretation met with the disfavour of the producers and he was replaced by Lane's understudy Brad Oscar before he could be seen by reviewers. He said: "I smile about it now. I was offered a big break on Broadway and I went there and took the role. "After talking with the guys behind the show, they offered me another job straight away in Washington DC. "I put it in perspective and just look at it as marketplace madness." But the roles have kept on flowing and he recently completed filming on director Ang Lee's new film Taking Woodstock. Starring the likes of Liev Schreiber, Emile Hirsch and Imelda Staunton, the movie marks 40 years since the iconic Woodstock Festival. Henry, who continues to teach and direct drama, sees both positives and negatives for the future of British theatre. He explained: "There is a certain excitement and buzz about it at the moment. "Ironically in a credit crunch, people feel they need to be turned on, move and transported - and they get that at the theatre. "In many productions there will be a realism and a toughness that people want to see to get away from their problems." But he is critical of the amount of funding that goes into British theatre. "Theatre people will always moan, but the actual amount that is put in compared to other countries is insane," he countered. Henry's acting talents have obviously been passed on as son Ilan is following in his father's footsteps. Ilan also attended RADA and has an up-and-coming career of his own, while Henry's daughter Carla is a student at Nottingham University.

|

HIT: As Manny Cussins in Damned United

HIT: As Manny Cussins in Damned United