|

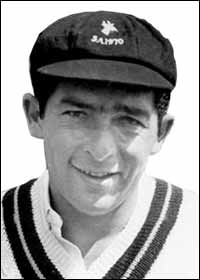

PROFILE Mistakes? Yes, but Ali is best Jewish cricket star of all time | ||

AS THE son of eastern European Jewish immigrants, Ali Bacher was not supposed to grow up to become captain of the South African cricket team.

Nor was he supposed to become one of the most influential figures in world cricket and draw the highest praise possible from Nelson Mandela. "Ali is a great South African who has brought pride to all of us," said the former South African president. Bacher was a handy Test batsman and his captaincy record reads delightfully. But the 70-year-old will perhaps best be remembered for his time as a supremely influential cricket administrator. Ali Bacher was born Aron Bacher in Johannesburg in 1942. His parents fled impoverished conditions for a better life in South Africa. His father left Lithuania in the late 1920s and his mother arrived in South Africa from Poland in the early 1930s. From a young age, Bacher had a keen interest in sports and excelled at everything he tried his hand at. He captained his football, cricket and tennis sides at school and scored his first cricket century at the age of 14. But cricket began to take over his life. Batsman Bacher also faced the tricky challenge of growing up Jewish in apartheid South Africa. He said: "Schools were predominantly gentile, but I belonged to a strong Jewish community. "At the weekends most of my friends were Jewish and I grew up in a Jewish area. I rarely encountered antisemitism. "There was one episode after a match when I was playing club cricket for Balfour Park, but a lot of the ethnic or racial hostility in the country was, as we know, directed elsewhere." Bacher rose through the first- class ranks and became a fully-fledged international cricketer. As a player, he was a scrapper and a fabulous fielder. He took over the national captaincy in 1970 when he was lucky enough to inherit what was probably South Africa's greatest side, including Barry Richards, Mike Procter and Eddie Barlow. Bacher skippered in only four Tests - and apartheid ensured they would be South Africa's last for 22 years. He won the toss each time, and completed a whitewash 4-0 victory over Australia. Despite his efforts, Bacher looks back somewhat modestly at his cricket achievement. He reflected: "We really had a fantastic side. To beat Australia 4-0 in those days was particularly special. "I am sure I would have played more had the world of cricket not banned us, but what is done is done. "The one regret about my playing time is that I never scored a Test century. To be honest, though, I am not one to live in the past. I rarely reminisce and think about my career." In 1970, the International Cricket Council voted to remove South Africa's Test-playing status as a result of apartheid in the country. This began the darkest period in the cricket history of a proud nation and Bacher regretfully played a role. Bacher helped organise rebel tours to the country during the 1980s at a time when South Africa's apartheid policies made it a sporting no-go area. Teams from around the world toured South Africa playing in unofficial games and Bacher now looks back with sadness at that time. He recalled: "If I knew then what I know now, I would have thought twice about organising the tours. "I had no idea how strongly the blacks in the country felt about the rebel tours. "At that time it was illegal for them to protest or make public their feelings. "So when the games were played we thought everything was fine and dandy. "We felt we needed to get the national side playing quality cricket against competitive teams. "Things changed drastically in 1989 when Mike Gatting brought his England team over. "Around that time, President FW de Klerk lifted the ban on protests and the hostility shocked me. I could not believe the intensity of the marches and rallies. "I saw the hatred towards us and it hit home how wrong we had been. "Everyone is entitled to make one mistake, but not the same mistake twice. "After the rebel tours I wanted to do my best to heal the country." Healing is exactly what Bacher did. To his credit, he reinvented himself as South Africa's cricket supremo when the previously separate black and white associations combined to set up the United Cricket Board. Bacher's reward came when his country vaulted back onto the international scene at the 1992 World Cup. He remained at the helm for the best part of a decade, before stepping aside to mastermind the organisation of the 2003 World Cup. His unique leadership skills both on and off the field are perhaps what Bacher is best remembered for. The batsman seemed to thrive under the responsibility of handling others. He admits: "I liked communicating and assisting people. "I loved getting the best out of people for the benefit of the team and lifting people's performances. "It was never the power that attracted me but the responsibility." Bacher was at the forefront of campaigns to bring cricket to developing areas of the country and help the nation's disadvantaged people. He helped provide new opportunities and a new lease of life for those who had no previous relationship with the sport and ushered it out of the dark ages. South Africa's readmittance by the ICC owed much to the tireless work of Bacher.

"When I do look back at my life it was the moment of democracy in 1994 that I feel most emotionally proud of. My interaction with Mandela is the biggest privilege of my life and being accepted back into the ICC was all part of the healing process. "It was also part of the dramatic change taking place within South Africa from a sporting, political and sociological point of view. "Setting up the United Cricket Board was a momentous occasion because it was the first time that blacks and whites had united to form a non-racial board." Bacher interacted with Mandela on many occasions and describes him as the "greatest South African of all time". "His capacity to forgive, but not forget, is extraordinary - he knew how important sport was in bringing whites and blacks together", said Ali. The work that Mandela, Bacher and many others put into taking South Africa out of apartheid is continuing to pay dividends now. Today, South Africa is seen as comfortably being the best Test cricket side in the world. Moreover, their squad is mixed in racial make-up. Bacher said: "The current crop of players is fantastic. "Look at talents like Hashim Amla and you can see why South Africa are considered the best Test team in the world. "When it comes to having more black Africans representing South Africa, we still need to do more though. Ntini was the first black superstar and hopefully there are more to come." Ensuring that enough black players featured for the national team was what drove Kevin Pietersen away from the country. The batsman believed his path to the side would be blocked by quotas so he instead elected to play for his adopted nation - England. This is a move that has made him deeply unpopular in South Africa and he receives a hostile reception when he returns. Bacher commented: "Lots of players left South Africa for other nations. Tony Greig and Kepler Wessels, for example. "They go with our blessing and they do not rubbish us. Yet Pietersen poured scorn on us. He is a magnificent cricketer who should be supported, but he is not. "That is because he did not understand the sporting revolution that was taking place in the country. Pietersen failed to grasp what was happening. "The reality is that players are today picked on merit and there are no longer quotas in place. He was very disrespectful towards us." Bacher can lay claim to being the greatest Jewish cricketer of all time and it looks as if his crown is safe for now. He added: "Unfortunately, there are not many good Jewish South African cricketers on the horizon. "They seem to have disappeared, but who knows. My grandsons age 14 and 16 are useful enough. However, the school system in South Africa is fantastic. "It means South Africa is set up to dominate cricket for many years to come. "The culture is strong, everything is mixed and there is a drive and desire to succeed." Although Bacher relinquished his roles in cricket, he always remains ready and available to help if needed. He is a proud Jew and says he would also relish the chance to work with the Israeli cricket board - but he is still waiting for the phone call. Since stepping aside from cricket life Bacher has been appointed chairman and a non-executive director of Right to Care. Right to Care is a non-profit organisation that supports and delivers prevention, care, and treatment services for HIV and associated diseases. Bacher's involvement will facilitate efforts to gain the support of high-profile people in the public eye and draw attention to Right to Care's contributions to managing the HIV epidemic.

|