|

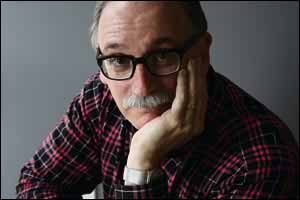

PROFILE Five years of research for Jim's Shoah 'masterpiece' | |

IT'S been hailed as a book you will never forget. The Washington Post calls it "a masterpiece" where American author Jim Shepard has created "something transcendent and timeless".

And fellow author Joshua Ferris said it is "full of wit, humanity and fearless curiosity". It is even predicted that Shepard, the acclaimed National Book Award finalist for his latest novel The Book of Aron, has penned something that will join the shortlist of classics about children caught up in the Shoah. Williams College teacher Shepard, the author of six previous novels and four collections of stories, was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, but now lives in Williamstown, Massachusetts, with his wife Karen and three children. The Book of Aron's narrator is an engaging, unhappy boy, struggling to survive in the Warsaw Ghetto in the final years of the Nazi regime. He and other children risk their lives by scuttling around the ghetto smuggling and trading contraband through the quarantine walls, in the hope of keeping their families alive as they are hunted by blackmailers, police and Gestapo. Aron, bereft of family, is rescued by legendary Janusz Korczak, a paediatrician renowned throughout pre-war Europe for children's rights who, once the Nazis take control, is put in charge of the Warsaw orphanage. Treblinka awaits them all. Shepard, 59, recalls the character of Aron forming in his mind after students and friends would often send him notes. "An old student asked me how come I never wrote about Korczak," he said. "I told him I have a wariness of writing saintly men and women as protagonists for any number of reasons. "I also thought that Korczak, a figure who is often considered a saint, was a strange position to write about. I think he was a fascinating character, but not one that would be the centre of any fiction I would write." However, the suggestion prompted Shepard to return to Korczak's yellow Warsaw diary, which he owns. "I'm the sort of strange person who owns books like that," he laughed. "My wife has said I'm the only person she knows who would take the history of the guillotine to the beach." When Shepard was reading through the diary, he came across a story of a boy whose mother had said she would stay alive as long as it takes to get her son into Korczak's orphanage. "Because Korczak's orphanage was very difficult to get into, she miraculously stayed alive for months until an opening finally appeared," he told me. "She immediately put her son in the orphanage and then died. Because of that, the son was inconsolable and screamed for three straight days." Re-reading the story, Shepard remembers thinking, "what would it be like to be in the presence of someone you know who has saved your life, and someone you are coming to love after their generosity of spirit, but at the same time be unable to fully appreciate what they are doing for you because you suffered so much damage and loss yourself? "That is where the genesis of Aron came from." As a non-Jew he says "it's enormously difficult to imagine writing about the Holocaust from the Jewish perspective - but it's also enormously difficult imagining writing about a woman's point of view or a child's point of view or even writing about yourself from 20 years earlier. "In some ways you are doing something hubristic in the service of trying to connect with another human being. "Part of what I try to remind myself is there's an enormous amount of hubris involved in almost any project of the empathetic imagination." So how easy, or difficult, was it to slip into the mindset of a 10-year-old boy? "Well, a boy of that age turns out to be much easier for me than most," he said, "and I attribute that to my own inner immaturity. "I think it helps to have not developed yourself if you're trying to write about children." Shepard also had an enormous fascination for the problems and potentialities of children and, since childhood, has been an observer of children, finding himself drawn to the subject over and over again. Why then did he choose to tell the story from the perspective of a child rather than from Korczak's point of view? He said: "There's a lot of advantages and disadvantages and one was being drawn to the way in which, by alluding myself to a single child's sensibility, I could first perceptualise a child's relationship as he tries to negotiate his world. "One of the difficult challenges facing me was coming to terms with a subject as enormous as the Holocaust and the way in which the impossible fact of the Holocaust makes children of us all. "I wanted to render the experience of one of those figures we wouldn't ordinarily single out as all that important, so I wanted to imagine a protagonist who everyone would consider the opposite of extraordinary and imagine his loss as terrible as well." The book took Shepard five years to research, but it was also buttressed by a long-time fascination with the subject. "Since I've always been drawn to catastrophe as a subject since I was a child, I've been reading about the Holocaust my whole life," he said. Once he settled on the subject, research began in earnest, mostly focused on ghettoes, orphanages and Polish childhood. He contacted survivors, American and Polish, and viewed extensive video archives. "The fact that survivors are depleting, it is useful to find any way we possibly can of re-engaging that narrative," he told me. There's a lot of Shepard's droll humour in the book and a number of people have commented, "boy, how courageous you were to inject humour into a story like this," he added. But he says, if one absorbs the primary documents, one very quickly discovers you don't have to inject humour into it at all. "One of the ways in which that uniquely eastern European Jewish sense of humour stood the sufferers in good stead, was by providing them with an ironic detachment from what was going on," he said. The Book of Aron contains a number of Hitler jokes and wry, bitterly funny asides that come directly from journals and diaries. Was there, in research, anything that astonished him? "One thing that surprised me, even after all the reading I did, was how much we tend to underestimate the extent to which the nature of the misery continually causes everyone to lower their horizons," he said. When asked if there is anything in his life that he wants to do, but hasn't already achieved, he replied: "Oh my gosh, I love your generous suggestion that I've already scaled Olympus. "There's an enormous amount I would love to do, but one of the reasons why I turn to research is because I do believe in the ability of the world to teach me. "I very much want to continue the project that is turning myself into a more interesting and more empathetic human being. "But in that regard I still think I have a long way to go."

|