|

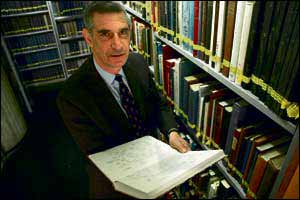

PROFILE Unlocking secrets of the past is dream come true for genealogist Neville | |

Having to endure that "poison lead" atmosphere was Glasgow-born Israeli diplomat Dr Neville Lamdan, who later rose to the positions of Israeli Ambassador to the UN in Geneva and to the Vatican. Dr Lamdan, who is now pioneering Jewish genealogy as an academic discipline as the founder and director of the International Institute for Jewish Genealogy in the National Library of Israel, recalled: "I turned to genealogy as a form of escapism from the poison lead atmosphere of the UN. "It took me to another time and another place. I began with my own family tree." After tracing his paternal family line back 300 years to Belarus and Russia, Dr Lamdan, who had gained his doctorate in history at Oxford University, realised that genealogy provided a "new way of looking at Jewish history". He said: "With my academic background I became very interested in making genealogy an academic discipline." It was way back in 1991 that Dr Lamdan first proposed the establishment of a Jewish Institute for Genealogy. His dream finally became a reality three years after he retired from the Israeli foreign ministry in 2003. Now Dr Lamdan does not want to dwell on his illustrious diplomatic career but is highly enthused about the recent successes of his institute, which is based at Israel's National Library on the Hebrew University campus. He told me: "This year we had three exciting developments. For the first time ever the World Congress of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem had a sponsored panel wholly devoted to Jewish genealogy. That is a real breakthrough. "Up to then academic Jewish studies courses were not quite serious about genealogy being genuine historical research. This prestigious conference gave us an entrée into that world." To add to that success, the Jerusalem Institute has awarded two research grants into the genealogy of Jews of Latvia between the two world wars as well as into Hungarian Jewry with distinguished scholars from all over the world working on the projects. And finally the Jerusalem Institute has been asked by a major American university to design BA and MA courses in the teaching of Jewish genealogy. Dr Lamdan says: "These courses, which can be easily expanded and offered elsewhere, should be on offer next year. "Genealogy is an extraordinary tool for teaching Jewish identity which is so important for Jewish continuity. When individual Jews work on their family trees and know their roots they develop their Jewish identity. "I hope that the institute will inspire both private individuals and historians and that its work will attract attention from many academic centres of Jewish studies." Dr Lamdan traces his own personal story back to Langside Drive, Newlands, Glasgow, where he grew up in the same street as the late Scottish- born Chief Rabbi of South Africa, Rabbi Cyril Harris. A keen member of the 93rd Norman Boy Scouts, Dr Lamdan, whose family name was originally Mandel, represented Scotland at the 1955 international jamboree at Niagara Falls. He says he has "very warm memories" of Glasgow where he still has friends. His first trip to Israel - as a British Inter-University Jewish Federation delegate to Israel's 10th anniversary celebrations - came as a graduation present from his father after he gained an MA in philosophy at Glasgow University. Attendance at the world conference of Jewish students gave Dr Lamdan an interest in the Middle East, so he went off to gain a second MA - Scottish students graduate a year ahead of their English counterparts - this time in Middle Eastern studies and Arabic at the University of Pennsylvania. It was then on to Oxford University where Dr Lamdan obtained his doctorate in modern history. His thesis was published as the book Arabs and Zionism before World War I. His "fascinating but unusual" diplomatic career then began with two years' service in London for the British Foreign Office. He was then posted to Tel Aviv as first secretary for years. Following two years back in academia in Oxford and at the Hebrew University, following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Dr Lamdan was invited to join the Israeli foreign ministry. He served for all of 30 years, ending up as Ambassador to the UN in Geneva and to the Vatican, after earlier postings to the UN in New York, Beirut and Washington. He also served in Jerusalem as director of the foreign ministry's Egyptian and North American departments and met his US-born wife Susan in Israel in 1973. As the wife of a diplomat travelling the world, she had to give up her first career as a biochemist at the Hebrew University and, as Dr Lamdan says, "re-invented herself as a computer programmer". On her retirement she has "re-invented herself" once again, this time as a tour guide. They have three sons and four grandchildren.

|