|

PROFILE Jewry in UK and Oz so alike, says rabbi | |

But at the start of his career this Oxford mathematics graduate told Lord Sacks, who was then Chief Rabbi-elect, that he "knew for sure" he did not want to be a teacher. It was the persuasive influence of Manchester's King David Schools supremo Joshua Rowe who charmed the Rabbi Kennard over the Pennines from being Yorkshire and Humberside student chaplain, which first brought Rabbi Kennard into teaching. But even then it was some time before he officially qualified as a teacher. Rabbi Kennard was born into a family which was extremely involved in Anglo-Jewish communal affairs. His late father Alan Kennard was president of the London Board of Shechita as well as heading various United Synagogue departments. But Rabbi Kennard, who attended a top London public school and only gained his early Hebrew education at Sunday morning classes, said that the primary influence which prompted him to devote his life to awakening Jewish awareness in the young came from the now-defunct Jewish Youth Study Group. He said: "My rabbis and teachers in the study group made a great impression on me." Rabbi Kennard's first taste of yeshiva life came with six months at Jerusalem's Beit Midrash L'Torah before going to New College, Oxford, to read mathematics and become involved in J-Soc. It was at an Oxford Shabbaton that he met his wife Vicky (nee Kerron), who came from a Liberal Jewish family with minimal Jewish observance but who was keen to explore her religious roots. Having been greatly influenced himself by a Jewish youth group, Rabbi Kennard decided to make informal Jewish education his career. His first step in that direction was as Union of Jewish Students education officer. On their marriage, the couple moved to Jerusalem to intensify their Jewish education. After three years at Brovender's Yeshivat HaMivtar, Rabbi Kennard went to a Jerusalem kollel where he gained rabbinical ordination after two years. His first post back in the UK was as Yorkshire and Humberside student chaplain, which he held for nearly five years. It was then that his preference for informal Jewish education was placed on the backburner. He said: "It all changed when I received a call from Mr Rowe to head Jewish studies at his newly- established Yavneh for girls at Manchester's King David High School. The rest is history." Rabbi Kennard moved from heading Jewish studies to the whole school but was aware of his lack of formal teaching qualifications. Vicky suggested to him that he take an Open University post-graduate Certificate in Education. But as he could not fit the hours needed for the course into his busy timetable, Vicky took it instead. Rabbi Kennard's educational salvation came in the form of Manchester Jewish Grammar School head Phaivish Pink's government-recognised teacher training scheme for those already teaching at Jewish schools. Rabbi Kennard says: "Mr Pink is my role model and mentor in the teaching profession." Wishing to broaden his horizons, in 1998 Rabbi Kennard moved to become head of Manchester's Broughton Jewish Primary School. But he missed a secondary school environment so five years ago he moved to head London's King Solomon High School . This was followed two years later by the call Down Under to head the co-educational Mount Scopus Memorial College with its nearly 1,500 pupils from kindergarten to the equivalent of our sixth form. So how does Australian Jewish and general education compare with the British model? He replies: "Jewish children and Jewish parents in the two continents are in many respects very similar. Australian culture has a lot in common with that of the motherland. Until very recently Australians felt themselves an extension of Britain." But one fundamental difference between the Jewish educational systems in the two countries, he says, is the fact that no Australian Jewish schools are state-aided. This means that they don't have all the current admission problems suffered by British schools in the wake of the JFS case. But it also makes Australian private Jewish education very expensive. He says: "There is no such thing as a state faith school in Australia. Even the Catholic schools are basically independent." So is the Australian Jewish community wealthier than its British counterpart? He replies: "Australian Jewry has a whole socio-economic range. The community is sometimes caricatured as being very wealthy. But that is not true.'' And how does Melbourne Jewry compare with that of Manchester to which it is sometimes likened? He says: "There is much more emphasis on Ivrit in which pupils are immersed right from kindergarten. All the Jewish content from kindergarten to the end of secondary education is in Ivrit. "The community is very Zionist, proportionately raises more money for Israel than anywhere else and sends a lot of people on aliyah." There are also fewer charedim than in Manchester and a much larger population of secular Jews. He says: "Australia hosts a very high proportion of Holocaust survivors and their descendants who are proudly secular and proud of their Yiddish culture. There is even a secular high school which teaches Yiddish." There is another difference between British and Australian schools. The man who originally opted for informal Jewish education has found it in his Australian school. He says: "There is greater familiarity and informality, a healthy rapport between teachers and students. Because of the Australian culture the children are friendlier and are more likely to say hello when they see their teachers." Although Rabbi Kennard's "long-term hope" is to return to Israel, he is really enjoying the Australian way of life. He said: "The people are very welcoming." The environment also feels safer with less crime and antisemitism. He says: "In Australia we have the impression that Britain is a hotbed of terrible antisemitism and anti-Zionism. But even here we have our Jewish anti-Zionists." In his little spare time, the rabbi gives shiurim and writes a column in a local Jewish newspaper. But there are signs that the freer life of Australia and its educational system may soon be coming to an end as it becomes affected by the more regimented British model. He says: "New national tests were just brought in. In the next couple of years we will have a national curriculum and a lot more centralisation. "I fear there may be more proscription."

|

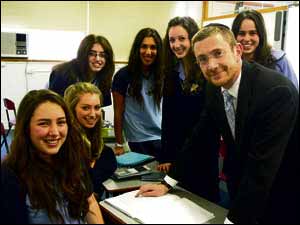

DOWN UNDER: A contented Rabbi James Kennard with girls of Australia's second largest Jewish school, of which he is head

DOWN UNDER: A contented Rabbi James Kennard with girls of Australia's second largest Jewish school, of which he is head