|

PROFILE Bracha spent 30 years trying to publish her autobiography | |

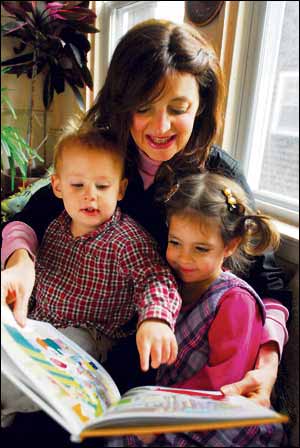

HARVARD graduate Bracha Goetz wanted to be a psychiatrist, specialising in anorexia.

As a student she was a feminist activist, speaking and writing about how women’s magazines cause anorexia by urging women to diet and have slim figures. But, all the while. Bracha herself had eating disorders to the extent that she stole from a roommate in order to maintain her bingeing habit. In desperation, she consulted a Japanese psychiatrist who encouraged her to seek her Jewish roots in Israel. That did the trick. Bracha, who stopped believing in God just after her 12th birthday, but experimented with Buddhism and Christian Science and nearly married a Catholic, is now the author of 36 children’s books, mainly for the charedi market. She is a mother of six and grandmother of 27. She has just published her candid autobiography, Searching for God in the Garbage, which took her decades to get published. “I have been working on getting the book published for the past 30 years,” she told me. “Secular publishers would love the beginning of the book, but not the end of it. Orthodox publishers were the opposite. I would get really great responses from the publishers, but with reasons why they couldn’t publish it.” The beginning of the book chronicles the life of a 1960s and 70s student, searching for spirituality in all the wrong places and becoming a Harvard feminist activist — hardly the stuff of charedi publishers. The second part of the book chronicles how a Jerusalem Aish HaTorah encounter changed her life and cured her anorexia — hardly what secular publishes want to know. She told me: “The book was going nowhere until last year I found a unique literary agent who is a religious Christian and was so into the book.” Now Searching for God in the Garbage has been published by mainstream W&B Publishers. Bracha said: “I was a little nervous before it came out about how people would react. It’s hard to reveal difficult parts of my past. But I did it to help others. “It’s been so wonderful. I feel I have deepened relationships with everybody. People are so much more open with me because I was open in the book.” Brach believes that spiritual craving is at the heart of many eating disorders. She said: “At the core of an addiction, there is a spiritual deficit. In regard to food addictions, for example, people can ask themselves the simple question, is it my body that is hungry or my soul? “If they ask themselves that question they will know whether they need physical or spiritual nourishment. Souls need nourishment. When we deny that, that’s when the problem starts.” Bracha came from a loving, liberal-minded New York assimilated Jewish family. When Bracha became a born-again Jew, her family were no longer so liberal-minded, using whatever pressure they could to lure her from what they considered to be a cult. But Bracha stuck to her guns. But she said: “Once the grandchildren came, my parents became much more supportive of the path I chose. They were very happy when they saw the life we had. “Before my mother passed away, she asked that my father should come and live with us, which I thought was really beautiful. My father had Alzheimer’s. “Even though he had not been religious, every day he would wake up and ask if it was Shabbat because he enjoyed it so much with the whole family around him.” Just after her 12th birthday Bracha wrote in her diary: “I am starting not to believe in God anymore.” Yet two years later she gained an A for writing an essay about the Gerer Rebbe! Even in her most Jewishly-alienated days Bracha had this uncanny attraction to chassidism. However, the same year as the diary entry, she went to a Buddhist centre with a friend and hated it. Two months later she went with a Jewish boyfriend to a Christian Science Church and was uplifted. She later could not understand why her liberal-minded parents objected to her Catholic boyfriend, whose home she went to for Christmas. As Bracha’s spiritual search progressed, so did her obsession with her weight. Aged 17, she commented in her dairy that her Seventeen magazine had dieting tips on one page, pictures of luscious chocolate cream cakes on another, followed by fattening recipes, accompanied by an advert for pantyhose displayed by a skinny model. She wrote in her diary: “God, I’m confused. Am I supposed to be skinny or eat?” Two months later, she organised a feminist meeting on the subject in her high school. The issue became more deeply ingrained when boyfriends dumped her when she put on weight. At Harvard, Bracha wrote feminist articles on the subject for the text book, Women Look at Biology Looking at Women, which was used in women’s studies courses at universities around America. She planned to study the subject academically. Yet her eating problems continued. She told me: “I was already becoming anorexic. That’s why I wanted to know more about it. I was so obsessed with weight, food and dieting. That’s why I started studying it. “My book shows that even if you have an intellectual understanding, it’s not enough. You can see you are obsessed and you can’t stop it. That is one of the purposes of this book. I was a very intelligent person with all these resources and yet it didn’t help me at all.” After a stimulating time in Harvard, Bracha went to South Carolina Medical School where all the students wanted to do was drink and party. Bracha’s bingeing became uncontrollable until Dr Wang told her that her Jewish soul was searching and that when she found what she was looking for she would be fulfilled. Working in Hadassah Hospital, she met up with “old-friend-turned-religious-fanatic” Mark Weiss, who lent her books and took her to Aish HaTorah classes. The rest is history. Bracha met her husband, Rabbi Aryeh Goetz, also a baal teshuva (returnee), at a Shabbat meal. They settled in the Judean Hills and began raising their family. At first Bracha, who still calls herself a feminist, tried to convince herself and others that raising a family and home-making was just as fulfilling as a career. But Bracha was not just a mother and home-maker. She was also a writer. She had never stopped writing throughout her life. At 12, she had a poem published in the national McCall’s magazine and she edited her high school newspaper. She wrote her first children’s book in a playground watching her own two little children. She said: “I would take my notebook with me to the playground. After I wrote my first children’s book, I put it in an envelope and sent it to America. “A few weeks later I got an answer that my book was being published. I realised that that was how you write a children’s book. I was very excited.” Bracha and her family returned to America “by accident”, she said. Nearly 30 years ago, they went for two weeks to visit her parents who weren’t well. They decided to stay and settle in Baltimore. After publishing 36 children’s books, some on subjects like preventing abuse, Bracha said: “I am very happy that some of my children’s books have been ground breaking. “As a baalat teshuva, I don’t just accept the status quo. I have changed my life so radically, so when I see things that I don’t think are right, I am happy to make things better. “I don’t have any shyness about saying when things are not going right. The Orthodox community was in need of picture books about personal safety for very young children.” Bracha is aware of problems in the community from being involved in a Jewish Big Brother Big Sister programme, which mentors problem kids. She said: “I see what’s going on and what needs improvement. I wrote a children’s book, Hashem’s Candy Store, about healthy eating, and Let’s Appreciate Everyone, sensitising children to students with special needs. “I hear that my books about personal safety, like Let’s Stay Safe and Talking about Private Places are actually saving lives. I am so happy. It’s amazing. “Children are reporting abuse. Children and parents now have a greater awareness about abuse. They are being much more proactive to prevent it. When it does take place, they are reporting it.” Bracha recently branched out from merely serving the charedi community and started writing children’s books on universal themes, which have been published by mainstream non-Jewish publishers. She hopes that Searching for God in the Garbage “will reach out to all kinds of people”.

|