|

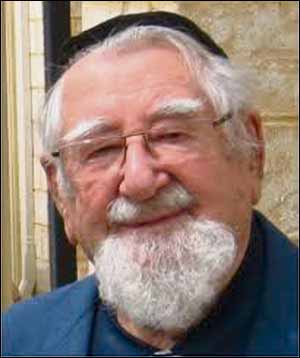

PROFILE Rabbi Dr Shalom Coleman showing no signs of slowing down — at age of 99 | |

EMERITUS Chief Rabbi of Western Australia, Rabbi Dr Shalom Coleman, is planning for his 100th birthday celebrations at the end of this year.

The doughty 99-year-old told me: “I am carrying on as usual. I am very, very busy with all sorts of things. I’m still preaching, still teaching. “I give lectures and shiurim on philosophy, Talmud and contemporary history and I’m sorting out my library. I’m active and keep up with all the contemporary news.” But he admitted: “But at the same time, I’m getting on for 100. Naturally, it’s a time when I have to pull in and slow down a little bit.” But he asked: “How can you do that when you have to do something with your life?” And that something includes, even at his age, thinking of others’ welfare more than his own. Speaking to me at the beginning of this week from a sweltering 34 degree Australian summer, he was extremely concerned that I keep myself warm, as he was aware of the cold which was gripping his native Britain. Rabbi Coleman inherited his rabbinic prowess from his forebears. His grandparents left their native Minsk for then-Palestine at the turn of the 20th century, when Shalom’s father, Rabbi Tzvi Simcha Kalmanovich, was a teenager who had witnessed his family home being burned in a pogrom. Tzvi studied to be a rabbi in Jerusalem yeshivot and received a shochet’s certificate from Chief Rabbi Avraham Kook. After marrying Fruma, he served as a rabbi in her home city of Ekron. Due to illness and the death of a child, Rabbi Tzvi decided to look for a new life in America, but only got as far as the UK, where he became a rabbi in Chester and Wrexham. The family later moved to Liverpool, where Shalom was born just three weeks after the 1918 World War One Armistice, for which reason he was given his peaceful forename. Shalom attended St Margaret’s Higher Grade and Oulton High schools and was a Princes Road Synagogue choirboy. His hobbies included football and rugby. Before joining the RAF, he graduated in semitics from Liverpool University. With the formation of the Jewish Brigade in 1944, Shalom was seconded to become a recruiting officer, for which he disseminated information on the proposed Jewish state. An ardent Zionist and member of the Jewish Agency, in 1945 Shalom was faced with a major career decision. The JA offered him a Jerusalem desk overseeing the work of Jewish chaplains, which would later have secured him a diplomatic career in the new state or he could return to Britain to advance his academic studies. Shalom chose the latter and continued his studies at University College, London and Jews’ College. A friendship with former South African Chief Rabbi Louis Rabinowitz led Shalom to take up a position in Potchefstroom in the Transvaal. Two years later, he left Potchefstroom for Bloemfontein Hebrew Congregation in the Orange Free State. In 1955, he returned to Jews’ College to gain semicha. Rabbi Coleman told me: “I had a wonderful life in South Africa. But it was a country which unfortunately had apartheid. “I didn’t go along with that sort of philosophy. It upset me. But at the same time it was a wonderful community.” So, in 1961, he decided to move to Australia and he has not looked back since. He said: “They have been so wonderful to me. When I arrived in Perth after two years at South Head Synagogue, Sydney, the community had only 3,500 members. “Now there are at least 9,000 Jews with four shuls and rabbis.” The rabbi boasted that 700 people attended a fundraising event last week, addressed by celebrity lawyer Alan Dershowitz. Rabbi Coleman said: “Perth is a big and flourishing Jewish community. I am very pleased to say that I laid the foundations of it.” But it wasn’t all plain sailing. When the rabbi first arrived in Perth, there was great resistance to him establishing kashrut standards and building a mikva. Catering was done by WIZO without kashrut supervision. Such was the antagonism to the rabbi’s attempts that, on the day of his silver wedding anniversary, excrement was delivered to his front porch. But with perseverance, Rabbi Coleman managed to set up alternative supervised kosher catering facilities. He met with similar resistance to the building of a mikva, but again successfully persisted. By the time of his retirement in 1985, the community had been totally transformed until, he said, “it became a model community”. He said: “I don’t believe you have to defend the Torah. It defends itself. Naturally I had to struggle against Reform and Liberal attitudes. “They did not understanding the bread and butter of Jewish identification such as a mikva or kashrut. “The people didn’t want to change and endeavoured to make me toe the line.” But he insisted: “You toe the line to Torah, not to its critics.” Rabbi Coleman holds no bitterness towards his former critics. He said: “I am not a person with any acrimony. I want to live a good Jewish life and try to teach as much as I can. It wasn’t their fault. “They were very isolated. But they are no longer isolated by any means. They are wonderful people.” Besides his work for the Jewish community, Rabbi Coleman also lectured in post-biblical Hebrew at Sydney University, where he gained his first doctorate and was a member of the Sydney Beth Din. He has lectured all over the world, including 26 years teaching biblical archaeology at the University of Western Australia. In 1981, he received a CBE and, in 1990, the Order of Australia, as well as a Federal Centenary Medal. He even has a dental clinic and cemetery park bearing his name. The Shalom Coleman Clinic was so called because of his position as chairman of the Dental Hospital Board and the Shalom Coleman Grove for his work for the Karrakatta Cemetery. He was also an active Rotary Club member and Freemason, representing both organisations at prestigious occasions, as well as a frequent broadcaster making TV appearances. His community are currently planning his centenary celebrations for Shabbat Chanucah.

|