|

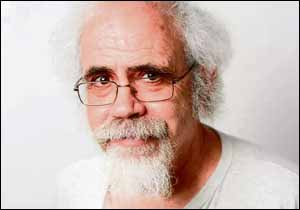

PROFILE Translator is making his Mark with Israeli words | |

MOST of Mark Levinson’s colleagues would agree that his ‘Translatable but Debatable’ blog — which analyses and elucidates Hebrew words and expressions — rings out clearly as his signature tune.

Mark is currently translating two books from Hebrew to English, “both Israeli stories set in the past, one factual and one fiction”. Massachusetts-born Mark came from an established Reform family with a strong Jewish identity. His grandmother was “a prominent activist” with the Hadassah women’s organisation. Mark majored in English, and by 1970 had a bachelor’s degree from Harvard, which his parents, brother and two uncles had also attended. “I figured a Harvard degree is a general stamp of approval and companies should be lining up to hire me,” he said. However, the job scene had suddenly become a wasteland. “Also, the country was becoming politically polarised and I didn’t feel comfortable at either pole,” Mark added. “And I noticed that the media were beginning to break the post-Second World War taboo against anything that might possibly offend Jewish people.” Another discordant note was the emergence of anti-Israel propaganda around the campus. Mark responded to these challenges by making aliya, even though “I’d never visited the country, couldn’t speak Hebrew and didn’t know a soul here”. He explains his youthful resolve as a desire to become a creditable Jew. “I didn’t want to embrace Orthodox Judaism by way of catching up with the generation before me and I didn’t want to learn Yiddish, but I wanted to do something,” he said. This radical change of environment involved attending ulpan while working for a year “on an assembly line for citrus crates” in Kibbutz Ramat Hashofet in the Menashe Heights, in the Megiddo region. Next he moved to Haifa to spend three years as an English teacher at night school, before the army drafted him. He stayed in the same profession there, first teaching English at the military academies and later teaching English and maths to a select group of “Raful’s kids,” disadvantaged soldiers who needed remedial education. Chief-of-staff Rafael (Raful) Eitan had taken the social initiative of rehabilitating illiterate and alienated youth through army service and career training. Despite the difficulties of this task, some of Mark’s students progressed well, and one now heads a regional council. Mark met his wife, Leah (nee Mizrakhi), before the army. Although she had attended his night school class, their relationship only developed later when her workplace at Haifa’s Interior Ministry was fortuitously close to his. “Leah grew up mostly on Moshav Ein Ha’emek and Moshav Geva Carmel,” Mark explained. “While I was in uniform, she provided constant moral support and advice, and we got married after my discharge. After we moved to Herzliya in 1981, she got a job there at city hall. “My wife is proud of being a Samech Tet (a thoroughbred Sephardi) and a seventh-generation Jerusalemite, born on Mount Scopus.” Her father fled Jerusalem “because he was suspected, correctly, of aiding the Hagana while serving with the British police. He recounted that during the War of Independence he drove the first truck that broke through to Jerusalem on the Burma Road”. The couple married in 1977, after Mark found suitable employment as a technical writer at Elbit. His mother was gratified when her son “married into a large, warm family”. As for Leah, “when she married me she thought she would finally perfect her English, thanks to me, but instead I improved my Hebrew, thanks to her.” Their son Shakhal, a software engineer working for a Herzliya startup, was born in 1980. Commenting on the hi-tech scene of the late 1970s, Mark noted: “The Israeli software industry was in its infancy then. I had no prior experience, but neither did the programmers. “I understood enough to understand that I didn’t understand enough, and persuaded Elbit to send me to a programming course.” There he learned the basics; but he refrained from seeking work as a programmer, because “it seemed that to restart my career at that point would be to take a step backward”. Because his next employer was Scitex, in the Herzliya industrial zone, the family relocated southward in 1981. Although Scitex had advertised for computer graphics trainees, “on finding I was a technical writer, they preferred to keep me in my profession”. He later expanded into promotional writing for them, and afterwards worked for other software companies. In total, Mark’s hi-tech career spanned 38 years. During his last position, he sidelined as a self-employed translator. “I’ve translated fiction, poetry, songs and drama, as well as journalism and routine business and advertising materials,” he explained. Nowadays, translation is Mark’s primary calling. When translating a book about acting, he realised: “A translator is an actor. Like any actor, I’m in the business of believably projecting an identity that isn’t my own”. Just as “the actor digs into personal memories to find some kind of emotional equivalent” for an unfamiliar experience, so when conveying “a word or phrase that doesn’t exist in English, I dig into our cultural memory to find some kind of equivalent”. Mark is concurrently involved with two established creative writers’ organisations. First is a 46-year affiliation with the Voices Israel Group of Poets in English, where he has served variously as editor-in-chief, branch chairman and contributor to its annual anthology of local and overseas poetry. Incidentally, his own poetry in translation won a citation from Mifal Hapayis in 2002. A smaller group where he has occasionally served as literary editor is the Israel Association of Writers in English, with its “core membership of professional-level poets and fiction writers,” and its annual journal called arc.

|