|

PROFILE Eli’s relative was king of Poland... for one day! | |

ELI Rabinowitz is a man on a mission. The South African-born film-maker, genealogist and blogger wants to unite Jewish and non-Jewish pupils all over the world through his Partisans’ Song Project.

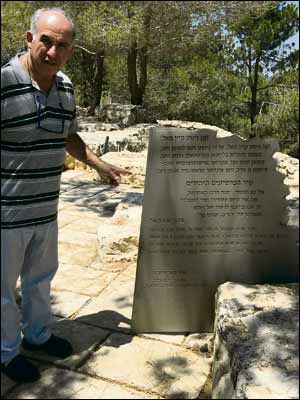

Eli, who now lives in Perth, Australia, wants to revive, in the younger generation, a love of Yiddishkeit, particularly in relation to the Yiddish-speaking elements who resisted the Holocaust in places like Vilnius and Warsaw. Retired fashion wholesaler Eli hit on his favourite song, that he wishes to promote all over the world, by accident. In fact, he became fixated on Jewish genealogy and international filming, also by accident. Ten years after moving to Perth in 1986 for business reasons, Eli became interested in simcha videography. He said: “The non-Jewish man who made my wedding film taught me a lot. He taught me how to interconnect people so that viewers could work out who the parents and grandparents were. I always had a camera in my hand.” His films became so popular that he began to do it professionally and offered his services in a voluntary capacity to film communal events. He also filmed Holocaust survivors’ testimonies. He said: “That led me into Yiddishkeit. I developed an interest in family history.” Eli’s father, who was a chazan in South Africa, had a lineage which dated back to 16th century Poland. Eli discovered that his 12th grandfather was Shaul Wahl Katzenellenbogen, who was reputed to be the king of Poland for a day. The story goes that Lithuanian nobleman Mikolaj Krysztof Radziwill (1349-1616) wanted to repent for his sins. The Pope advised him to live as a beggar for a certain number of years. At the end of that period he was rendered penniless. The only person who helped him was Rabbi Samuel Judah Katzenellenbogen, of Padua. In return for the favour, the rabbi asked the nobleman to find his son Saul, who was studying in a Polish yeshiva. Radziwill was so impressed with the young Torah scholar that he allowed him to live in his castle, where his fame grew. On the death of Polish King Stephen Bathory in 1586, the country was split between two contenders to the throne. To solve the dispute Saul was appointed temporary king for a short space of time. Armed with such fascinating family histories, Eli’s interest in genealogy knew no bounds and he began to write webpages for JewishGen’s KehilaLinks. He was particularly fascinated by the story of his third great grandfather, Avraham Shlomo Zalman Zoref, who came from Keidan in Lithuania and was a disciple of the Vilna Gaon. He was a member of the Gaon’s Perushim movement, which left Lithuania for the Old City of Jerusalem at the beginning of the 19th century. At that time, no Ashkenazim were allowed to settle in the Old City because 100 years previous an Ashkenazi had not repaid a debt to an Arab. Zoref disguised himself as Sephardi and used his diplomatic skills with the Turkish authorities to get the debt annulled. He then went on to rebuild the Old City’s Hurva synagogue and reclaimed Jewish lands from Arab creditors. But his activities also brought him enemies and he became the first recorded victim of Arab terror when, in 1851, he was struck on the head with a sword on the way to morning prayers. His name heads the list of Israeli terror victims read out annually on Yom Hazikaron by the Prime Minister. Since 2011, Eli has been visiting Poland, Belarus and Lithuania annually in search of interesting genealogical stories. He said: “Through genealogy, I get connected to everybody else which I love.” Eli was particularly interested in stories from his family’s Lithuanian home of Keidan. Then, he received a request from a non-Jewish school teacher in Keidan, who had seen one of Eli’s wedding videos online and wanted to teach her pupils about the life of the Jews who used to live in their city. Eli visited the city and met up with Liana, who asked him to produce a Chanucah film for her. Eli filmed it in a Jewish school in Lithuania, with a service led by a Chabad rabbi. The film was seen by the rabbinic head of Johannesburg’s large King David Schools, who asked to meet Eli when he was visiting family in South Africa. The rabbi told him that every year on Yom Hashoah pupils sang Zog Nit Kein Mol, the Partisans’ Song. But because it was in Yiddish, the pupils did not understand it. The rabbi asked Eli to explain its significance to the high school’s 1,000 pupils. The song was written by young poet Hirsh Glik, a member of the United Partisan Organisation in the Vilna Ghetto in 1943. The poet died the following year, but his song became the rallying cry for Jewish partisans to never stop fighting Nazi oppression. It was also sung by Jews in other ghettos and concentration camps as a gesture of hope and resistance. It was even sung in Yiddish as a protest song by black singer Paul Robeson at a Moscow concert in 1949. Eli hit on the idea of producing video links between children all over the world who would sing the song and explain its significance in this day and age when Holocaust survivors are dying out. With the help of ORT schools in Ukraine, Russia, Moldova, Lithuania and Estonia, as well as pupils at Jewish schools in Australia and South Africa, Eli produced films featuring pupils from all over the world singing the song in Yiddish, Hebrew and English. Now he is set to cast his net even wider so that next year’s Yom Hashoah commemorations featuring the Partisans’ Song will spread to the UK, Europe and America. Eli says: “With the decline of Yiddish and the loss of survivors, I am allowing children all over the world to connect with each other and with their history.” He is particularly critical of Holocaust memorial ceremonies in Israel and the UK which feature modern Hebrew or English songs. He maintains that it is important that secular children, as well as their religious counterparts, reconnect with their Yiddish heritage and show resistance to the forces of fascism which are currently raising their ugly heads once again. For him that can be achieved through the Partisans’ Song.

|