|

PROFILE Mother’s pain in Holocaust inspired Gaby to write novel | ||

THE pain is clearly etched across Gaby Koppel’s face as she recounts the memories of her mother’s alcoholism.

“I had a love-hate relationship with her, but I think about her every day,” Gaby tells me over coffee at MediaCity UK, Salford, where the producer is working on the new series of BBC One’s Rip Off Britain. “When she died, I had terrible guilt because I think I treated her quite badly. “I had to do that, though, for my own sanity — I had to put distance between us. “My mother was quite emotionally manipulative and needy, too, which was probably because of what she went through.” Gaby’s mother, Edith, hid with her family in Budapest during the Second World War. If that wasn’t traumatic enough, she was later raped by a Soviet soldier. Edith eventually got out of Hungary and made her way to Paris before ending up in Cardiff, through family connections. There she met Heinrich Koppel, whose father had seen the writing on the wall for Jews in Germany and left in 1933. Edith only revealed what she had been through when Gaby was in her 20s. “For one moment, I stopped deeply resenting her and being really angry with her, and saw things from her point of view,” Gaby said. “She was drunk a lot and I spent much of my adolescence clearing up after her, but it was clear she found life a real struggle. “If you read accounts of the Holocaust, it usually notes that life before it was perfect, but it wasn’t always like that. “Families were dysfunctional before, during and after the Holocaust. “I don’t know why that should be a revelation, but nobody will say it.” Her thoughts and feelings on such matters led Cardiff-raised Gaby to pen her first novel, Reparation, to be published by Honno Welsh Women’s Press in February. Set in 1997, it tells the story of Elizabeth’s eccentric, often inebriated, émigré mother Aranca, who is approaching retirement. Her novel solution is to seek compensation from the Hungarian government for what she suffered during the war. In the wake of her father’s sudden death and her mother’s increasing obsession with wartime Hungary, Elizabeth is struggling to keep her job and her relationship afloat. Then she receives a phone call to say that her mother has been arrested in Budapest and Elizabeth is forced to confront the nature of motherhood, love and loss as she puts together the clues to Aranca’s past. Gaby, who started writing the book while she was taking a Master’s in creative writing at London’s City University, explained: “I wanted to think about the Holocaust from my mother’s point of view. “I read books about what happened to Hungary’s Jews, especially from 1944, when the Nazis invaded. “What my mother must have gone through was horrendous, but the book isn’t a historical novel — it is about the psychological after-effects and how that can affect subsequent generations. “The Holocaust lives on long after the people who experienced it have passed on. “As a TV producer, I have worked on Holocaust Memorial Day events and spoken with many survivors. “They kind of turned their experiences into something which made them great people, but you never really know what happens indoors, at home. “I want to challenge the preconception that everything becomes noble, because it does get antsy and the emotional consequences can be extremely horrible.” The only other Jewish pupils at her primary school were her brother Robert, and two distant relatives. Ironically, as most of her contemporaries had no idea about Jews, they regularly called Gaby’s father a ‘Nazi’ because he was German. She knew, though, that her family was different to others and described growing up in a “mittel-European” environment. Gaby, 61, recalled: “Our dads would take us to cheder and then get together and have coffee, like in the coffee houses in Budapest. “Only the men were allowed in the room, while the women gathered in the kitchen. “My mother was quite tall, chain-smoked with a cigarette holder and when I came out of school, she would be standing there regally, waiting for me. “My mother and father thought British food was terrible, which it was, and they couldn’t understand why culture was put on a pedestal, instead of being part of every day life. “My dad didn’t get multiculturalism, to him Goethe, Schiller and Mozart were culture — end of. “We belonged to the local Reform synagogue because that was made up of continental refugees, while the Orthodox shul was for English Jews, whom my mother said were ‘not like us’.” After reading English at the University of Sussex, Gaby worked as a journalist in Brighton before becoming a regional researcher on the BBC current affairs programme Nationwide. She then moved to London to work on the BBC’s flagship Breakfast Time programme, before moving to Thames Television, which her parents thought was a “much more Jewish company because David Elstein was at the helm”.

But things started to go badly for Gaby in the early 1990s. Firstly, Thames lost its franchise as the way local television operated changed and then her father died — three months after she and her filmmaker husband Stephen Brown’s first child, Rivka, was born. “I was out of work and the mortgage rate was at 15 per cent because there was a massive housing crisis,” Gaby said. “We had negativite equity for a while and, even though my husband was working, our bank account was empty at the end of every month. “We probably did take it out on each other, but staying together and making it work was the best thing we did.” In 1998, Gaby’s mother was found dead at the age of 69. She had made a number of suicide attempts, leading to an inquest, which declared Edith’s death to be of natural causes. Gaby, who is also mother to Sarah and Dovid, endured more heartache after Sarah was born, as she was diagnosed with a heart condition and spent time in Great Ormond Street Hospital. “I was working for the BBC at the time, but luckily the Central Line ran straight from Great Ormond Street to White City, where the BBC was,” she said. “I would feed Sarah and then go straight to work and walk into work crying because I would have scenarios going around in my head in which Sarah died. “After her first operation, Sarah was given a 75 per cent chance of survival, which was higher than average, but didn’t sound like good odds to me.” Thankfully, Sarah is now fine and healthy. Gaby — who runs video production with her husband — suffered a health scare of her own in 2004 when she discovered she was a carrier of the faulty BRCA2 gene, which is extremely common among Ashkenazim. She was later diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy. Her paternal aunt had died of ovarian cancer and she had cousins diagnosed with breast cancer, so she had her ovaries removed, too. In an ideal world, Gaby — who has produced numerous documentaries and series, including Crimewatch, A Place in the Sun, Salvage Hunters and Michael Portillo’s Great Continental Railway Journeys — would spend six months making TV programmes and the other six writing books. “Unless you’re really, really lucky, writing books isn’t a real money-spinner,” she said. “It is something you do because you’re passionate about it and you feel you have more to say. “I want to write about my father’s family next. His grandmother remarried, so I want to explore the different relationships, including my aunt, who had an intense love affair with her stepbrother.” Unlike many other survivors, who would never return to their countries of origin, Gaby’s mother regularly visited Budapest, holidaying there with her husband and sister-in-law. “My dad didn’t feel hostile to Germany, either,” Gaby continued. “I remember being at a Jewish youth camp when I was 16 and an Israeli boy told me his parents could never buy anything German-made. “I thought, ‘why on earth not?’, because that kind of thinking just wasn’t a thing for me. “My dad was a German engineer and thought that German engineering was the best in the world.” Gaby is also hoping to raise the issue of mental health with regards to her book. “When she died, I asked people what they thought of my mother and most of them said to me, ‘ach, she meant well’,” Gaby recalled. “People didn’t understand mental illness like they do today. “My mother would travel to London twice a week to see the psychotherapist Ilse Helman, a colleague of Anna Freud’s, whose specialism was refugee children.” Follow Gaby on Twitter: @Gabykoppel

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|

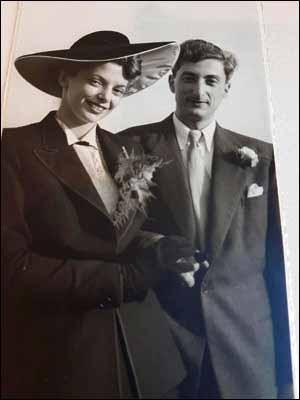

DIFFERENT FAMILY: Edith and Heinrich Koppel

DIFFERENT FAMILY: Edith and Heinrich Koppel