|

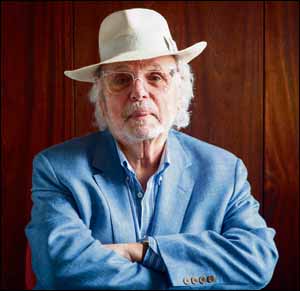

PROFILE How Laurence helped life turn Hunky Dory for ‘unknown’ Bowie | |

Yet the man who launched David Bowie’s career and who was behind a ground-breaking legal case which freed songwriters from unfair exploitation is quite the opposite. Softly-spoken, modest and good-humoured, it was not until the last few years that Laurence, who is now a sprightly 83, decided to write about his hugely-successful life. “I wrote it mainly because I would say to my grandchildren, ‘did I ever tell you about so and so’ and they would say, ‘do us a favour and write a book about it — probably to shut me up,” he told me from his London home. The result is Hunky Dory: Who Knew? (B&B Books, £20). “The title says it all because I never kept any material or anything, so a lot of it was based on what I could remember,” Laurence laughed. “Luckily, a lot of the people I worked with wrote about themselves or had books written about them and they do say if you are writing a book and use stuff from another it is plagiarism, but if you read 10, it is research.” His achievements are a long way from his early years. Of Polish and Russian descent — the family’s original surname was Myerovitch — he lived in London’s East End until he was 11 when the family moved to North London, where his parents set up a confectionery and tobacconist shop. Having left school at 16 to train as an accountant, Laurence supplemented his studies by running a sweet stall on Sundays in the East End. He qualified as an accountant in 1960 then set up Goodman Myers and Co Chartered Accountants with friend Ellis Goodman. But his big break came four years later when Laurence agreed to represent record producer Mickie Most, who needed an accountant. Among the artists he represented were The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Animals, Herman’s Hermits and Jeff Beck. It was a boom time for music and he decided to take the plunge in 1970 when he left accountancy to pursue a full-time career in music, setting up the Gem group of companies. Its first release was Edison Lighthouse’s Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes), which reached number one in the charts. And among Laurence’s numerous signings was a young David Bowie. “Bowie was signed to a record company, but he was not successful and not happy with his management,” Laurence recalled. “His lawyer, a guy called Tony Defries, brought him to me and said he would like to work with me.” Laurence went on to invest his own money that led to a deal with RCA Records — and albums Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust. “I invested £75,000 in him, which, at the time, was a huge amount,” he said. “We pressed 500 copies of the Bowie promo and one was sold just recently on eBay for £10,000! “David and Tony later fell out hugely and we went our separate ways as he always associated me with Tony, but I saw David in later years and he was always very amicable.” The original ideas, however, just kept flowing and in 1972, after creating Arcade Records, Laurence came up with the idea of selling compilation albums in the UK. “The company doing it in America was called K-tel, which was also Jewish-owned,” Laurence explained. “In those days in the UK you couldn’t record songs from the radio. “I used to do it because it was the business I was in, so I would choose a compilation for a party I was putting on or something. “One of the many problems was that some of the record companies did not want their artists sharing a record with other artists. “For example, if you were Led Zeppelin, you didn’t want your song on the same bloody album as Donny Osmond. “It was unique because this was the time before (The Who’s) Tommy and Pink Floyd’s concept albums and because, back then, it was all about selling singles.” He persevered and went on to pioneer the production of compilation albums, with one of them, Elvis — 40 Greatest, selling more than a million copies. Nowadays, songwriters are royally rewarded. However, it was not always that way, until Laurence became involved in — and masterminded — the 1974 Macauley v Schroeder legal case. Tony Macauley, who was behind such hits as Love Grows and Don’t Give Up On Us, had signed a publishing deal with the Schroeder record company which, although legal, was, as Laurence put it, “an unbelievably unfair deal”. The case was eventually won in the House of Lords and it helped “free” songwriters. “It was the most important thing I did in business,” Laurence claimed. “I am very proud of it and the fact that it is now a prescient case which has changed everything for songwriters, whom I love.” Despite his success, Laurence, who has been married to Marsha for 57 years, began to get itchy feet and, by 1980, was interested in entering the theatre business. In 1974, he had set up GTO Films and began to produce and distribute movies, including The Greek Tycoon, Scum and Picnic at Hanging Rock. The catalyst for change came when Laurence attended a punk rock gig in Camden. He recalled: “I did a deal with RCA and one of their bands was a group of punks called UK Subs, so I thought I should go and see them. “There were all these punks in the moshpit, spitting and bumping into each other. “Next to me was an archetypal punk, with a mohican, chains and drinking beer. “I’m standing there and then, suddenly, he vomits and all the sick is running down him on to his Doc Martens, which bounced on to my Gucci loafers! “The thing was that he didn’t move — he didn’t say ‘ugh’ and move away, he just carried on drinking. “That was it for me and I knew it was the right time.” The father-of-three and grandfather-of-seven subsequently went into theatre production, taking shows to the West End and Broadway, and working on huge productions such as Hairspray, End of the Rainbow, The Seven Year Itch and Mack & Mabel. “I was told putting on musicals in the West End was the same as quite liking medicine and thinking of doing brain surgery,” he added. “It was enjoyable, though, although films were a struggle “You have to remember that in the 1980s, nobody was really interested in British films, apart from Chariots of Fire, which the Americans went mad for, although Porky’s II actually made more money.” After more than 30 years, however, he has returned to the film industry, with his latest role being an executive producer on Judy, which stars Renée Zellweger as Judy Garland, released this week. It is based on his Tony Award-nominated hit musical End of the Rainbow. Laurence, who secured the film rights, said: “The musical was phenomenally successful “It is very rare that a show in the West End, Broadway or wherever is made into a film — to even have one is lucky. “I got David Livingstone, who made Pride, as a producer and he was the one who signed Renée Zellweger. “It has received standing ovations and I am very proud of it.” He is keeping his finger in the film pie, too, as a script he has penned, about an ageing rock star who plans to perform his final gig at Butlins, has been optioned by Great Point Media. Laurence and his brother Roger, who co-founded Punch Taverns and Cafe Rouge, were raised in a “very traditional” Jewish family. And, although he describes himself as secular, he is a member of the West End Synagogue. “I narrated the audio book of Hunky Dory and thought to myself, ‘I sound so bloody Jewish’,” Laurence laughed. “I support synagogues because if people like me didn’t, there wouldn’t be any and I want there to be synagogues. “There is a wonderful book by Deborah Lipstadt called Antisemitism, which I bought for each of my grandchildren because it explains antisemitism easily. “What she said about Jeremy Corbyn — who makes me sick — was that he will support any man with a rock in his hand against a man in a tank, irrespective of whether that is right or wrong. “He just thinks of the ‘poor Palestinians’ being oppressed by the Israelis, but has no idea about Israel’s history. He is evil.” Laurence never experienced antisemitism in his career, although felt a hint of it when he produced a play called Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell, which starred Peter O’Toole. “He did not like me, although I don’t know whether he had antipathy towards Jews because he was very Arabist due to making Lawrence of Arabia,” Laurence said. “I think he suffered badly at the hands of some Jewish film producers, as well.” One well-known Jewish person he had a run in with was music mogul Don Arden. Born Harry Levy in Manchester, the father of Sharon Osborne had a fearsome reputation. “I was looking after The Animals and they had not been paid by Don after a tour,” Laurence recalled. “I went with Mickie Most to see him and told him that he owed my clients money arising from their last tour and if he didn’t pay them I would issue a writ. “Don responded: ‘listen, you little pisher — if you don’t get out of my office I am going to throw you out of the window’. “We met many times after that and got on well.”

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|