|

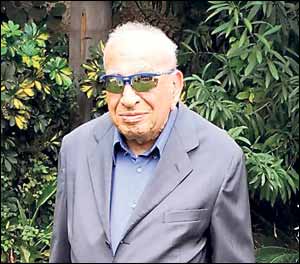

PROFILE Israel’s ‘James Bond’ rescued over 130,0000 Iraqi Jews | |

Running for one’s life, hoping to escape a country that sought his life, did not help. Heart pounding, the man’s sweat quickly evaporated into the dry desert air. As instructed by Israel’s precursor to today’s intelligence agency, Mossad, the undercover shaliah of Mossad LeAliya Bet crouched behind a berm at the end of the runway. It was almost 1.30am. Head shaved by a jailer and with two broken teeth, his body ached from recent blows; his battered face was swollen. Making his way through a swamp to the hiding place, he was covered in mud. After more than two years of work posing under numerous false identities — including Habib, Zaki, Nissim, Salman, Nouri, Noa, Dror — his cover was blown. A commercial plane full of passengers taxied to its place for takeoff. Pausing to flash its lights, the signal was given. Dashing out, exposed and in the open, Mordechai Ben-Porat raced to the aircraft’s tail where, he was told, a rope would be dangling. He would have to climb to freedom — if it was there, that is — and if the secret police did not appear, if the pilot and crew did not panic, if he had the strength to shimmy up the thin and prickly cord. Arrested three weeks prior, he had been chained and brutally tortured for information. Subjected to beatings, nakedness, sleeplessness, innuendo and threats, his cell mates — murderers and thieves — were sympathetic. His tormentors were compelled to relent only when a Muslim attorney, Yousif Fattal, convinced a judge to grant him bail, including a little extra for the magistrate. Within days of being freed, he answered the summons to the equivalent of a small claims court. That judge, infuriated that the defendant, a Jew, had not been disciplined when a drunken bicycle rider hit his car, sent him back to prison. When once again his release was obtained by Fattal, Ben-Porat knew his days were numbered. If he did not get out of the country, his real identity as an Israeli emissary would be revealed. He would be hanged. While being escorted by an armed warden to Iraqi Secret Police Headquarters, he slipped away in a crowded market. Hidden by friends, he urged Mossad LeAliyah Bet to find a way to get him out of the country. There was also intelligence to share. While being tortured, Dror (one of his more common pseudonyms) had gathered information instead of revealing it. What he learned would save the lives of the remaining fellow Jews who still lived in a land to which they were sent into exile 2,400 years ago. With the rebirth of Israel as a nation in 1948, Jewish prosperity and status dissipated with shocking swiftness. About 10 years earlier, Hitler’s Islamic ally, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, poisoned the minds of Muslims in Iraq against the Jews with whom, for the most part, they had lived in harmony for hundreds of years. Al-Husseini saw the rise of Zionism and, convinced it would bring Jews back to their homeland, sought to oppose them on every front, including Baghdad. When, in fact, Israel was born in 1948 and the Arab state coalition that waged war against it was defeated, members of that coalition, including Iraq, were bitter. Blaming fellow citizens, regarding them as collaborators with Jerusalem, Iraqi Jews became targets for discrimination even to the point of death. The Iraqi government banned emigration to Israel, declared Zionism a capital offence and arrested hundreds of Jews for trying to leave the country. As Ben-Porat ran toward the plane, he at first saw no rope. Only as he approached the tail did it appear. Recalling the adventure, he wrote: “Thanks to my training in the Haganah and the help of the navigator, John Owen, I clambered up.” Born in Baghdad on September 12, 1923, the eldest of 11 children, Mordechai made his way to Israel three years before it was established. There, he joined the Haganah. After serving with distinction in the War of Independence, he was recruited by the Mossad LeAliyah Bet for “a sensitive and dangerous mission with a great deal of responsibility”. “I don’t have to tell you in what a state the Iraqi movement is now,” the Mossad LeAliyah Bet interviewer told Ben-Porat. “You were there, you came from there. The community is in a bad way. People are being persecuted and are eager to arrange for their emigration to Israel. “We want you to fly over there in order to help them leave the country. You are Iraqi by birth, well versed in Arabic and familiar with the Iraqi Jewish dialect. “You understand the Iraqi mentality. You are also familiar with the work of the Haganah. You have a command background. You certainly are the right man for us.” Thus commissioned by the nascent Jewish state, Ben-Porat returned to the land of his birth, to Baghdad, in 1949. His mission? To help Jews who needed to escape make their way home to the land God deeded to them through Abraham some 3,000 years ago. “On 20 November 1949, I was on my way to Basra,” Ben-Porat wrote in his book, To Baghdad and Back. “Dressed in Bedouin robes I crossed the Shatt-El-Arab waterway on a small boat with an outboard motor, accompanied by the smuggler Haj Aziz Ben Haj Mahdi. Neither my friends nor my parents would have recognised me in the black agal and keffiyeh adorned by a thick mustache on my upper lip.” At first he organised illegal escape routes for Jews fleeing persecution. Usually, refugees crossed the border to Iran from where they made their way to Israel. It soon became clear, however, that almost all of Iraq’s Jews would have to leave in order to live. What Mordechai developed to address the matter became known as Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. The operation, named for the biblical prophets who led exiles back to Israel in the 5th century BCE, was a massive, messy task. Working with Iraq’s parliament and ministers, Mordechai developed a plan for exodus by air. The logistics and political maneuverings were daunting. Airlines had to be recruited, property and businesses sold or held in trust. Money had to be paid on every side, including bribes to police and politicians, fixers and informers. Communication channels had to be established within Iraqi Jewish communities, with Jerusalem, with international partners, and with Iraqi officials. It is a miracle any of it worked. Everywhere he turned, Ben-Porat encountered visceral opposition. The worst of it did not come from Iraqi antagonists, but from fellow Iraqi Jews. Resentful of Mordechai’s authority bestowed by Israel, one key leader of the Jewish community in Iraq increasingly opposed his leadership. Things became so bad the whole project almost came to a grinding halt. While the exodus was happening, right in the middle of displacement and transfer, the Iraqi authorities almost stopped planes from landing in Baghdad to fly refugees to Israel. There were problems from Jerusalem, too. The new state did not have infrastructure for absorbing more than 100,000 refugees. Who would be in charge of their orientation? Where would they live? How would their property be handled? These and thousands of questions like them often meant things were not well thought out. Officials in Jerusalem had almost no real understanding of realities on the ground in Baghdad. The only bridge between the two cultures was Ben-Porat. Every day there were reasons to give up, good reasons. Opposition was relentless, but if the job wasn’t done Ben-Porat knew that, on the heels of the European Holocaust, there likely would be a Middle East holocaust, and that simply was not an option. In fact, out of an estimated 137,000 Iraqi Jews, Ben-Porat’s leadership of Operation Ezra and Nehemiah resulted in about 130,000 making their way to Israel. An estimated 111,000 came by air, the rest by way of Iran. Roughly 7,000 Jews chose to remain, hoping to protect businesses and assets. Today, however, there are no Jews living in Iraq. Upon his return to Israel, Mordechai married his fiancé, Rivka, with whom he had three daughters, 15 grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Until her death in 1995, they were married for 49 years. Today with his wife of 20 years, Nechama, he lives in Ramat Gan. In subsequent service with Mossad LeAliyah Bet, he was involved in other missions, most of which remain top-secret. Among other things, he also became an MK; and founded the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Centre in Or Yehuda. In 2001, he was awarded the Jewish state’s highest civilian honour as a recipient of the Israel Prize with specific reference to his efforts rescuing Jews from Iraq. Recently, those same Jews, along with their children and grandchildren, gathered at the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Centre. Their nickname for Ben-Porat? Israel’s James Bond. Today at 96, Mordechai sits at his dining room table, remembering the past, but doing so as a lens for viewing the future. Reflecting on all he experienced in times of intense persecution in Iraq, he looks at developments in today’s world. His conclusion? His sober conviction is that persecution has returned and likely will appear with no less intensity throughout the world, especially of Jews, Kurds and Christians. Should he establish a school that will teach the things he learned – how to survive, what to do, what not to do? He is giving the matter serious consideration. Perhaps the greatest mission for Israel’s James Bond is yet ahead. Perhaps in 2020, the construction of The Mordechai Ben-Porat International School of Persecution Preparedness will begin. (Jerusalem Post)

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|