|

PROFILE ‘Anonymous Soldier’ was sent to London to assassinate Bevin | |

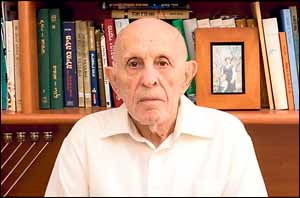

His room is neat and well-kept, his Filipino carer Joy refers to him as Saba, and visitors, both family and friends, are frequent. One might take the friendly old gentleman that greets you at the door with ‘Dr Heruti’ engraved on it as just another nonagenarian retiree; clearly in fine shape for a man of 93, but perhaps remarkable in no other way. This impression, however, would be mistaken. A little over 70 years ago, Ya’acov Heruti stood at the cusp of an act that, if carried out would have earned him a prominent place in the history books covering the first days of Israel, and the twilight of the British Empire. That act was the planned assassination of the then-British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin. The assassination was to be carried out by a paramilitary structure which Heruti had established on British soil at the order of Israel freedom fighters Lohamei Herut Yisrael (LEHI), of which he was a member. Bevin had made himself hated by the Yishuv in Mandate Palestine for his pro-Arab actions, his opposition to Israel’s establishment and the frequency of his antisemitic rhetoric. But his planned killing was only one of a series of assassinations for which Heruti had been dispatched to London. At 21, Heruti was already a seasoned operator for the LEHI, smaller of the two Jewish paramilitary groups engaged in the struggle against Britain. One of Avraham ‘Yair’ Stern’s “Anonymous Soldiers”, as the LEHI founder, slain in 1942, termed his fighters in the poem that would become the movement’s anthem. Registered as a law student at the University of London, Heruti had spent the previous months building the covert structure that lay behind the planned killing of Bevin. This apparatus was by early 1948 poised and ready for action. To understand how Heruti came to be standing at the head of a paramilitary network in the British capital, it is necessary to look a little further back, to Mandate Palestine in the last months of 1945. The London cell, for all its dramatic aspects, was only one chapter in a long career that saw Heruti recruited to the LEHI while still in his teens, fighting in Jerusalem’s Old City in the War of Independence, active in a revived underground organisation in the 1950s, (falsely) implicated in the killing of Dr Rudolf Kasztner, and later prominent in a number of nationalist political initiatives. Born in Tel Aviv in 1927, Heruti’s father, Mordechai, was a supporter of Mapai, forerunner of today’s Labour Party. Having become convinced while still at school of the need for action to expel British forces from Mandate Palestine, his first contacts were with the larger Irgun Tzvai Leumi (IZL). Before he could be recruited, however, a LEHI operative arrived uninvited at his house. The LEHI man had been informed by Heruti’s friends of his intentions, and he quickly persuaded the eager 18-year-old of his movement’s seriousness. “My contact said that the IZL were ‘vegetarians’,” Heruti recalled. “The IZL at that time didn’t attack soldiers — only property. LEHI did. British soldiers, on condition that they were soldiers — yes. In LEHI, they said a la guerre comme a la guerre (war is war), and in war, all means are permitted.” The organisation rapidly identified its new recruit’s particular talents, and Heruti was detailed to its “technical department”. This was the body responsible for the production and development of explosive material and devices, and for the repair and development of weaponry. “So one day, ‘Shmuel’ (Yehuda Levy, commander of the LEHI technical department) came to me and asked if I knew how to prepare explosive material,” Heruti said. “I’d always been good at chemistry, so I went straight to the Chemists’ Association and I asked for a book on explosives. If they’d been tailing us then, they could have stopped it right at the start. But it didn’t interest anyone. “There was only one old Jew there. The first book I got was called Qualities of Explosive Material, and I learned the difference between good and bad explosives. Dynamite, for example, explodes if you shoot at it. TNT doesn’t. “The material I looked for, and found, was in good condition and convenient for being moved from place to place.’ Heruti took on responsibility for the production of explosives for LEHI. Within a few months, the materials he prepared began to be used with telling effect against installations of the Mandatory government. On April 26, 1947, LEHI operatives placed a device containing the explosives prepared by Heruti at the British police station at Sarona. Four policemen, including one officer, were killed when the explosives were detonated. As the tempo of operations increased, the organisation began to need higher quantities of material. As Heruti recalls: “I was responsible for preparing the explosives for LEHI, until the point where we went from preparing it in a bucket on a roof, to something on a larger scale — semi-industrial. Then Shmuel took it into his own hands. “I finished the job at the point where we could produce something like eight kilos of explosive material.” Building the cell in the UK was his next mission. Heruti’s objective there was to assassinate three men — Bevin, former commander of British forces in Palestine General Evelyn Barker, and Major Roy Farran, who had tortured and killed a young LEHI member, Alexander Rubowitz, in Jerusalem. He arrived in London in October 1947, possessing neither money, means nor infrastructure for the carrying out of this mission. The first task was to begin recruitment. Heruti met with Yehuda Ben-Ari, a veteran of the Jabotinsky movement resident in London. From Ben-Ari, he received details of a number of organisations broadly in sympathy with the objectives of the IZL and LEHI. He then began to establish contacts with members of these groups, and to invite the most promising individuals to become part of the infrastructure he was building. As he recounts: “From the point of view of building underground organisations, this is the worst way you can do it. But I had nothing.” The organisations in question included the Betar youth movement, and the ‘Hebrew Legion’ group, an association of Jews who had served in the British armed forces and were sympathetic to the Jewish paramilitaries in Mandate Palestine. Slowly, the infrastructure began to take shape. “By chance, I met a number of young Jews,” Heruti continued. “We didn’t have a great deal to lose, and we began to organise. And slowly, slowly, ‘a friend brings a friend,’ and we started building up an infrastructure, addresses, a place for storing weapons . . . Many people, and many whose names I won’t reveal even today.” Among the names that Heruti is willing to reveal is the late Eric Graus, who became a senior figure in Anglo-Jewry. “Eric Graus, for example,” Heruti remembers, “had a place where we could receive mail from abroad. And that was how we received explosive materials —quite poor explosives, by the way — dynamite.” The explosives were mailed from America, the first of them arriving inside the hollowed-out batteries of a radio set. The sender was Benjamin Gefner, a LEHI member resident in New York, where he had organised the ‘American Friends of LEHI’. While all this was taking place, Heruti was pursuing his legal studies at London University, and getting to know the city. He makes clear in his book, One Truth, Not Two, that LEHI’s war was not a general one against the British nation as a whole. This orientation also affected operational decision-making. With regard to the main target — Bevin — the organisation decided to avoid use of explosives out of concern that innocents could also be affected. Instead, a conference of foreign ministers in central London was chosen as the site for the attack. An escape route was identified. Surveillance was carried out. “The plan was to hit him outside the meeting of foreign ministers, then escape on foot to Piccadilly Circus,” Heruti recalled. But with preparations complete, and Operation Simon ready to go, Heruti received a terse communication from Israel. “A message came from Nathan Friedman-Yellin (the LEHI operational commander at the time), calling it off. As to why — I had no idea,” he said. Plans for the assassination of Bevin were immediately stood down. With the main mission cancelled, the cell turned its attention to the other two targets — Barker and Farran. Letter bombs were sent to the addresses of both men. In Barker’s case, the device was defused by police after the general’s wife noticed it had a strange smell, and decided not to open it. Regarding Farran, the British officer’s younger brother, Rex, opened the parcel addressed to him, and was killed by the explosion. “A frustrating failure,” as Heruti terms it in his book. “We were looking for the murderer — not his brother.” “Then the mission ended,” Heruti said. “The 1948 war was beginning. Students were being called back to Israel. I already wanted to get out of there.” The LEHI cell in London was shut down and ceased operations. On his return to Israel, Heruti was dismayed to find that his mentor in the LEHI’s technical department, Yehuda Levy (‘Shmuel’) had been executed, accused of treachery. A long and eventually successful battle was waged by Heruti and other former comrades of Levy to have his name included in the list of LEHI’s fallen fighters. Heruti then took part in the battles for Jerusalem, and was decorated for rescuing a wounded Hagana fighter under fire during a clash with the Jordanian Arab Legion. He said: “I went to Jerusalem to fight, and not to Brigade 8 because Yitzhak Shamir sent me, and I owe him this. Do you know what it was to fight in Jerusalem at the time of the siege? A celebration!” Heruti was briefly caught up in the round-up of LEHI members carried out by the new Israeli government of David Ben-Gurion, after the assassination of United Nations mediator Folke Bernadotte. Following the British departure, the establishment of the state and the subsequent War of Independence, confirms Heruti, “LEHI had no further reason to exist”. A short attempt at organising a political party failed. The triumvirate that had led the movement (Shamir, Nathan Friedman-Yellin and Dr Israel Eldad) went their separate ways. Heruti, for his part, remained active in Israel Eldad’s “Sulam Circle” in the 1950s. In 1952, dismayed at the security situation in Jerusalem, he organised a new underground movement together with another former LEHI member, Shimon Bachar. The ‘Malchut Yisrael’ underground carried out an attack on Arab Legion forces near the Damascus Gate. Heruti and Bachar, also in 1953, placed an explosive device in the courtyard of the Soviet legation in Tel Aviv, to protest the persecution of Soviet Jews in the “Doctors” Plot and Slansky show trials at that time. He was sentenced to a 10-year term for these activities but was pardoned in 1955, and qualified as a lawyer in 1956. His final brush with the authorities came when Heruti was accused of involvement in an alleged “terror organisation” behind the killing of accused Nazi collaborator Dr Rudolf Kasztner in 1957. He was acquitted of these charges in January 1958. Heruti’s public activities continued, however, in tandem with his law practice. After 1967, he became deeply involved in the process of land purchase for Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria. He was among the founders of the Tehiya Party in 1979, and was subsequently close to Rafael Eitan’s Tsomet list and Rehavam Ze’evi’s Moledet Party. He remains a member of the Board of Governors of Ariel University, and an active supporter of a Chabad school providing vocational training and academic studies in Ashdod. (Jerusalem Post)

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|