|

PROFILE Prof wants Israel and Hamas to be friends | |

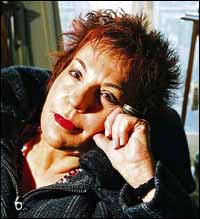

When Sorbonne professor of modern Jewish history Esther Benbassa published her small book To be Jewish after Gaza last year, she was naively surprised at the popularity it received. She was invited non-stop on to French TV shows to propound her criticisms of the Jewish state in which she had once lived and studied. Esther told me: "I love Israel. But because I am so attached to the country, I defend the Palestinian cause." And she defends it to such an extent that she is blaming the EU for not putting enough pressure on Israel to make peace. She says: "Peace can't be made without Hamas. Israel has to make peace with its enemies. "After the war in Gaza the French were really angry with Israel. But we should not confuse criticism of Israel with antisemitism." Esther maintains that the reason why Israel is treating the Palestinians so badly is because they are inflicting similar "suffering" on the Palestinians as the Jews suffered in the Holocaust. This, she feels, stokes up antisemitism. That is the theme of her book Suffering as Identity - The Jewish Paradigm, which stirred up controversy in French Jewry when it was published there and which has just been translated into English. I asked her about her own Jewish identity and what it was about French Jewry that led her to make this controversial allegation. Esther wasn't born in France, although she has studied and taught there since 1978. She was, in fact, born in Istanbul to a Sephardi family, dating back to the Spanish expulsion, who had previously lived in the Balkans. But like the children of other wealthy Jewish families in that part of the world, Esther was sent to a French-speaking school, making her a Francophile from infancy. She said: "My mother was from Salonika and my father from Bulgaria. My family were not religious but they respected traditions. They went to synagogue on important occasions, but my mother did not keep kosher. "We spoke French at home. I was very influenced by French culture." At the age of 15, Esther left for Israel where some of her mother's family had already arrived. After spending some time on a kibbutz, she studied French literature and philosophy at Tel Aviv University, after which she transferred to Paris University for her post-graduate studies. She told me: "I wrote two doctoral theses. The first was on French history. But then my father died. "I was very sad and thought that maybe I should write the history of my own culture. So my second thesis was on Sephardi culture." But although she has written several books on the history of Sephardi history and founded a research centre into the subject, it is as though she has paid her dues to her father's memory and background and moved on to become more universal in her approach. She fights daily against racism, including antisemitism, the cause of which she sometimes puts squarely on Jewish shoulders, due to their obsession with the Holocaust. Esther told me proudly: "I have now stopped writing about Sephardi history. Last week, I published a Dictionary of the Racism of Exclusion and Discrimination. It is already a bestseller." Esther is also proud of the fact that although she is "not at all religious", she is the first woman to hold the Sorbonne chair in modern Jewish history. She says: "The chair was founded in the 19th century. Most of the professors before me were religious men who wore kippot." So if she's not religious, what does being Jewish mean to her? She replies: "Jewish ethics and positive Jewish history." And she adds: "Jewish history does not begin with the Holocaust. "Some Jews consider that all Jewish history is that of persecution. That is negative." Esther explained the peculiarly French background to what she termed as the "sacrilisation" of the Holocaust, turning it into a secular religion. It all began with the 1791 Jewish emancipation in which individual Jews were regarded as "French of Mosaic persuasion". This meant that they could behave as Jews inside, but not outside. A change in the composition of French Jewry began in 1962 after Algerian independence when, as former citizens of a French colony, Algerian Jews had the right to enter France. Esther said: "When they arrived they had sad stories of exile. But no one wanted to listen. The Holocaust was not part of their identity as it was for European Jews." The influx of North African Jews into France accelerated following the Six-Day War. Esther maintains that this influx resulted from fear and not actual expulsion as many suggest. In France, these Algerian Jews became politically right-wing as regards Israel and, she maintains, "because of their anger over the Six-Day War, they wanted to share the Holocaust history of the Ashkenazi Jews of France". She feels that Holocaust consciousness in France led to a change for the worse in the Republic's attitude to ethnic minorities. Esther went on: "When Jacques Chirac admitted France's responsibility for the Holocaust in 1995 it was the first time the Republic gave recognition to a particular community''. She said: "I fight against this sacrilisation of the Holocaust which has attracted most of French Jewry who are not religious." She demands: "It must stop. The Masada syndrome of concentrating only on Jewish suffering is fuelling the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, which, in turn is linked to antisemitism. "It has to be stopped because this antisemitism is making life in the Diaspora much more difficult. "If the Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues, antisemitism will grow everywhere." It is no wonder that, with views like these, Professor Benbassa is the bete noire of the French Jewish establishment. Suffering as Identity - The Jewish Paradigm is published by Verso (£14.99)

|