|

THE GREATEST EVER JEWISH FILMS Vinz refuses to resort to simple stereotype | |

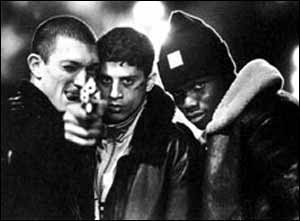

His 'fracture sociale' trilogy -Métisse (1993), La Haine (1995) and Assassin(s) (1997) - firmly places Jews in a present-day Parisian working-class milieu, far removed from the professional stereotypes usually found in Anglo-American film. In this way, Kassovitz's films reverse preconceived notions of Jewishness as he refuses to resort to the simple stereotype. In La Haine (The Hate) Vinz (Vincent Cassel) is a working-class Ashkenazi banlieue dweller; his best friends are black and North African. Vinz is a blond, blue-eyed Jew. With his skinhead haircut, he resists the very stereotype of the Jew. He postures as tough. He behaves in a way atypical for filmic Jews: punching, spitting, picking his nose and breakdancing. From the moment we meet him, Vinz is obsessively fascinated with weaponry: he fantasises about killing, forming his fingers into a pretend gun that he fires into the bathroom mirror, while mimicking Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (in French). Vinz festishises a gun he has stolen from a cop. He carries the gun with him at all times, keeping it tucked into his trousers. Despite the risks associated with doing so, he shows it off to his friends. He talks about avenging his friend, Abdel, who was killed by the police during a riot. Vinz is ejected from the spaces that professional Jews typically occupy in film. This is clearest in a scene in an art gallery, precisely the sort of upper middle-class arty space in which cinematic Jews are located. Vinz's clothes and speech disclose that he does not belong. And, in a further irony, the owner of the art gallery is played by Kassovitz's father Peter who, although nowhere explicitly identified as Jewish, for the culturally-aware spectator able to recognise the codes it further reinforces the Jewishness of the space from which Vinz is excluded. But Vinz is an ambivalent figure. The film juxtaposes contradictory images to convey his ambivalent status. Unlike his beur and black friends, he is able to pass as white, thus escaping the police brutality that is directed against non-white minorities in the film. In a dream sequence he breakdances to klezmer music, coding the clash between his Jewish and street identities. Vinz can only exercise his power in private and in his imagination, emphasised by his inability to use the real gun. When he is confronted with a bleeding, powerless skinhead who attacks his friends he is unable to shoot him. In a further irony the skinhead is played by dark-haired Jewish Kassovitz himself. Vinz's weakness is emphasised in another sequence. He and the 'pure' French drug dealer, as implied by his Gallic name, Astérix, compare guns hidden deep inside their trousers. Astérix then challenges Vinz to a game of Russian roulette and Vinz is found wanting in this respect as he loses his nerve. As Vinz leaves, Astérix demonstrates how he surreptitiously neutered Vinz's weapon, publicly reinforcing Vinz's inferiority and feelings of humiliation and defeat, compounded by the waiting policemen on the street outside.

|

TRIGGER HAPPY: Vincent Cassel, left, as Vinz in La Haine

TRIGGER HAPPY: Vincent Cassel, left, as Vinz in La Haine