|

PROFILE Rabbi wants Shabbat restaurants and transport | |

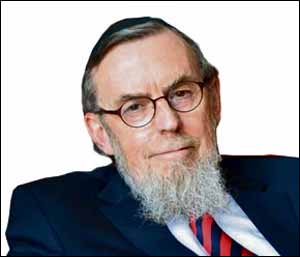

RABBI Dr Nathan Lopes Cardozo positively revels in thinking outside the box.

But then Rabbi Cardozo, whose autobiography, Lonely But Not Alone, is to be made into a TV documentary, has an unusual family history which affords him the unique stance of being simultaneously both an insider and outsider of Jewish tradition. As his surname would suggest, Rabbi Cardozo's paternal family comes from a long line of proud Sephardim. His great-great-grandfather, Rabbi David Cardozo, was Chief Rabbi of Amsterdam's Portuguese-Spanish Synagogue. But his mother was not halachically Jewish. Orphaned at an early age, Rabbi Cardozo's mother, Rebecca, was adopted, but not converted to Judaism, by his father's family. But she was brought up considering herself a secular Jew. His parents married just days before the Germans entered Holland in 1940. In fact it was her non-Jewish status which helped Rebecca save the lives of practically all her husband's family, as she sheltered them in her home, in the same building as Nazi collaborators. Rabbi Cardozo, who was born in 1946, said: "I was born by breech delivery, a very painful procedure, which my mother endured with iron strength. "We nearly did not make it. It was Friday night and I was born to two marvellous people who, by Jewish law, would not have been allowed to marry. "The physician was a religious Jew who had to violate Shabbat to save our lives. In many ways, both these facts - an unusual birth and being the child of a mixed marriage - have set the stage for my life. "I often see things from a reverse position. What is normal for others' evokes in me feelings of wonder and what others consider amazing, I see as obvious. I became somewhat of an in-out-sider. "My atypical beginnings have influenced my thinking in unconventional ways and, to this day, get me into trouble with some of my rabbinic colleagues as well as with religious and non-religious Jews." Growing up in a secular Jewish home, Rabbi Cardozo had too many unanswered questions about Judaism. He read widely, exploring all the major religions. But Judaism was in his DNA. At 14, he decided to become Jewish. He told his father he wanted to attend synagogue on Shabbat. But Saturday was a school day. The rabbi's father objected as Nathan's schoolwork had already been affected by his Jewish search. So Nathan decided that if he had to go to school he would try to keep Shabbat as much as he could. His family then lived in a small town called Aerdenhout. It was a 20-minute bike ride to his school which began at 8am. On winter mornings it was dark. One Shabbat morning he decided not to put his bicycle lights on. He was stopped by a policeman who told him that if he could not turn on his lights he should walk to school, which he did, arriving very late. Then Nathan refused to write in that morning's exam. His teacher, who was school vice-principal, listened to Nathan's explanation of his desire to become religiously observant and persuaded his father to allow him to attend synagogue rather than school on a Saturday morning. It was in shul that Nathan met his future wife Freyda. Her family and that of the local rabbi welcomed him into their community. At 16, Nathan was converted to Judaism and later studied at Gateshead Yeshiva for eight years. Rabbi Cardozo described his Gateshead experience as "an enormous culture shock". He said: "The religiosity was so different from my completely secular background. But I got used to it and started to appreciate it. "The teachers understood my background and did everything in their power to help me. The studies were very interesting, the people very nice, the teachers outstanding, but I did not fit in completely to the religiosity." After Gateshead, Rabbi Cardozo and his growing family returned to Holland, where he served as a student rabbi in The Hague. He turned down a request to become Chief Rabbi of Holland to make aliya. In Jerusalem, he taught at Ohr Somayach Yeshiva, during which time he expanded his philosophical and Jewish studies, including some from Conservative and Reform sources. While remaining true to Orthodoxy, Rabbi Cardozo came to see that "the narrow reading of charedi Judaism did not tell its entire story and even caused it to stagnate". He wanted an "authentic, rebellious Orthodoxy that would correct its mistakes, stop acting defensively and start being creating and daring". He even dared to quote a Reform rabbi in class. His rabbinic colleagues were not amused. He then defended Rabbi Shlomo Riskin when the latter got into rabbinic trouble for questioning Moses' leadership abilities. The crunch came when Rabbi Cardozo dared to challenge left-wing politician Shulamit Aloni to come up with valid criticism of the Orthodox. Rabbi Cardozo was threatened by the yeshiva with cherem (excommunication). He fought the cherem, but left the yeshiva world. He now says: "Nothing would have been more beneficial to me than to have been put under a ban. Many more of my books would have been sold and my ideas disseminated. "Looking back, I realise leaving the yeshiva was a blessing. I was able to develop my ideas independently and felt great relief. I was not any more in the official mainstream Orthodox world." Rabbi Cardozo founded his own institute, the David Cardozo Academy, in memory of his illustrious ancestor. The academy, he says, "is a place where we try out new ideas within Jewish tradition to give it new meaning and relevance. "Our lectures focus only on controversial issues. We don't do the normal stuff that everybody else does. We deal with big philosophical and halachic problems, how and what we need to do to change halacha to update it to the conditions in which we live today." Rabbi Cardozo feels that most Jewish laws were developed defensively in the Diaspora and are not particularly geared to the modern State of Israel. He said: "For example, since all shops and restaurants are closed on Shabbat, many people who are not religious complain they can't go anywhere. "We suggested opening some restaurants on Shabbat and running them according to the laws of Shabbat. "We could have Bnei Akiva youngsters working there on Shabbat." According to Rabbi Cardozo's idealistic plan, customers would not have to pay for their Shabbat food, which could be sponsored by big food companies like Tnuva and Strauss. A more practical plan might be to have halachically-permissible Shabbat transport, run along similar technological lines to Shabbat lifts, which are the norm in Israel. Rabbi Cardozo said: "If people want to see their parents on the other side of town or want to visit a hospital, they would be able to do so without having to violate Shabbat." There would be no payment for the tram which would run slowly at fixed, but fairly long intervals, covering the main parts of the city. The trams would be Shabbat appropriate with walls adorned with suitable Torah quotes. Rabbi Cardozo would like not only to make Shabbat observance easier and more attractive for the masses of irreligious Jewish Israelis but, as a convert himself, is very concerned about the fate of Israel's 300,000 Russians in Israel, who are not halachically Jewish. He said: "They are marrying into our Jewish society, but not through rabbanut. If you apply strict halacha, many will not convert because they don't want to or because it is too strict. "One has to make it as easy as possible for them. If they don't convert, they, their children and grandchildren will stay non-Jews. In 50 years, we will have a million non-Jews in Israel. "That would be very dangerous." Rabbi Cardozo would like to set up outreach programmes to these non-Jewish Russians to attract them to Judaism. He would also like to make conversion easier for them so they only have to keep all the biblical laws and not necessarily all the rabbinic ones. His views on the supremacy of the biblical laws over the rabbinic laws also affect his opinions on shemita, which he says, biblically is not incumbent upon the State of Israel until the advent of the Messiah. Rabbi Cardozo does not approve of the present arrangement of the heter mechira in which the land of Israel is nominally sold to a non-Jew for the shemita year. He said: "It is not healthy to sell the land of Israel to non-Jewish Palestinians. We should not do it." Not all Rabbi Cardozo's unconventional views make Jewish observance easier. For example, because he does approve of the halachic loophole of selling to a non-Jew, he does not sell his chametz over Pesach, but gets rid of it entirely. Rabbi Cardozo's life and views will be the subject of a TV documentary to be produced by award-winning Dutch filmmaker Willy Lindwer. It will be screened next year in Israel, Holland and America.

|