|

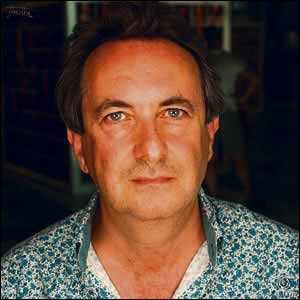

PROFILE Tim's Ukraine adventure to discover why war happens | |

REVOLUTIONS, wars, coups - Tim Judah has been at the thick of it all. From the aftermath of the Ceausescus' downfall in Romania to the war in Bosnia to the removal of Saddam Hussein, he has witnessed it.

But before his first posting abroad - Romania in 1990 - journalist Tim worked for the BBC World Service, where he found himself cutting tapes and "endlessly phoning Romania". It was not what he wanted to go into journalism for. "Nicolae Ceausescu (the Romanian communist dictator) has fallen and a revolution was taking place and I was just cutting tapes," said Tim, who is now The Economist's Balkans correspondent. "The Times foreign editor got in touch with me and said they had positions available in Karachi, Bucharest or Santiago. "I chose Bucharest, which eventually segued into my covering the Balkans wars." Ceausescu and wife Elena were executed by Romanian soldiers on Christmas Day, 1989. Tim, wife Rosie and new-born son Ben moved to its capital, Bucharest, shortly afterwards. "It was a fascinating time," he said. "The Romanians were so friendly. "They had been closed in and isolated for so long, but were full of hope, so it was a good time to be there. "And, of course, there were so many stories to be had. No journalist had been able to report properly in Romania." Tim's most recent adventure took him to Ukraine, where he made his way from the Polish border in the west, through to Kiev and then to the eastern front-line near the Russian border as war waged. It led to him penning his new book, In Wartime: Stories from Ukraine (Allen Lane, £20). Tim will speak about his book with author son Ben - who is also featured in this week's Jewish Telegraph - in London on Sunday, February 28 (12.30pm) as part of Jewish Book Week. "I had written a few pieces about Ukraine for the New York Review of Books, just before the Maidan Revolution," Tim added. "Allen Lane asked if I wanted to write a book about the situation. "When I looked into it, there actually had not been too many books written about Ukraine. It is a mixture of reportage and interviews. "I wanted to know what Ukrainians actually thought and why they were so angry. "I wanted to find out why war happens, without it being a dull, political science textbook." Tim was raised in London by an Indian-born father, a descendent of Baghdadi Jews who had moved there, and a Berlin-born France-raised mother. He is a member of the Spanish and Portuguese Sephardi Congregation, London, which he attends on High Holy Days. From an early age, Tim knew he wanted to work in journalism. "My dad was in the shipping industry, but I knew I did not want to do that," he recalled. "I always had an interest in history and had edited the school magazine." Tim graduated from the London School of Economics and also took a Masters at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, Massachusetts. He went on to work for the BBC African service, which was part of the BBC World Service. While in Romania, Tim began to make trips to Yugoslavia, where war was in the air. "Croatia and Slovenia declared independence and I never really went back to Bucharest," Tim explained. The family moved to Belgrade, the Yugoslavian capital. "The country was like California at the time - it was prosperous and developed," he added. "The communism there was different than in other countries, but because Yugoslavia was made up of six republics, it began to break down. "I was doing what I wanted to do - seeing history develop in front of my eyes." At the beginning of Tim's time there, he covered the sieges of Dubrovnik and Vukovar, as well as the war in Bosnia. Tim also interviewed the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžic and Ratko Mladic. Both were eventually accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide after thousands of Bosnian Muslims were butchered. "Looking back, I believe Karadžic was a bad person who waded into a situation, while Mladic was clinically insane," Tim pondered. He also covered the Srebrencia massacre, in July, 1995, where more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims, mainly men and boys, were killed. "Like Auschwitz has become the great symbol of the Holocaust, the same can be said of Srebrencia with regard to Bosnia," Tim surmised. In 1995, the family returned to London, but made frequent trips to the Balkans, where he wrote for The Times and The Economist, among other publications. Tim was also in the thick of it when war broke out in Kosovo in early 1998. The Kosovo Liberation Army, made up of ethnic Albanians, went to war with Yugoslavia over the territory, with the latter claiming it was Serbian land. The KLA was supported by NATO, which also bombed Belgrade. "I think there was a direct link between what happened in Srebrenica and Kosovo," Tim explained. "There was guilt in the West over what happened in Srebrenica - there was a feeling the Bosnian Muslims were not protected and thousands of them were killed. "NATO moved quickly to take action against the Serbs because Srebrenica hovered in the background." His time in Yugoslavia and Kosovo led to Tim writing two books, The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia and Kosovo: War and Revenge. Shortly after 9/11, Tim covered the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan. "It was an eerie experience in Kabul (the Afghan capital)," he recalled. "There were lines of bodies on the road, presumably of Taliban who had been executed." And while he met a few Jews while covering the Balkans, he had an amusing anecdote concerning the Jewish community of Afghanistan - all two of them. "These two guys literally hated each other," Tim laughed. "They had reported each other to the Taliban and both of them lived in an old synagogue complex in Kabul, but did not talk to each other." A piece he wrote which related to his background came when Tim was in Iraq, covering the fall of dictator Saddam Hussein in 2003 - and he was there when the statue of Saddam was pulled down in the centre of Baghdad. Those images were beamed around the world and became iconic. Iraq is Tim's paternal ancestral home and he went with one of the few Jewish families left there to visit the tomb of Ezekiel, which he wrote about. "I did feel worried about my surname," Tim recalled. "I remember going to the Jordanian embassy to get a visa for Iraq - because you had to go through Jordan to go there - and they asked me if my background was Palestinian. "Apparently Judah is also a Palestinian Jordanian name in Arabic, although they write it as 'Judeh'. "Because of my surname, it is one of the reasons I have not covered a lot of Arab countries - I would feel uncomfortable." The father-of-five has also visited Israel on holiday, but believes that he could not cover the conflict there objectively. "I have already carved out a niche for myself plus, journalistically, the Israel-Palestinian situation is one of the most covered areas on the planet." Tim spent around two years working in Ukraine. The crisis there began in November, 2000 when then-president Viktor Yanukovych suspended preparations for the implementation of an agreement with the European Union. The decision resulted in mass protests by its opponents, who became known as the "Euromaidan". Yanukovych was ousted from power by the protesters in February, 2014. However, unrest developed in the largely-Russophone eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. An ensuing political crisis in the region of Crimea led Russia to annexe the region in March, 2014. "A lot has changed in Ukraine," Tim explained. "The difference is that war exhilarated something which was already beginning insofar as that Ukrainians were becoming more ethnically Ukrainian and speaking Ukrainian." He also encountered a number of Jewish Ukrainians. "I know that many associate the Ukrainians with antisemitism because of the Holocaust," Tim added. "Of course, terrible things were done by the Ukrainians to their Jews, but a lot of Ukrainians saved Jews, too, which is not as well-known. "Ukraine today is not the same as the country of pogroms or during - and before - the Second World War." Tim spent Pesach 2014 with the Jewish community in the eastern city of Donetsk. "I was supposed to go home, but a colleague said I should go to Donetsk, as there was a good story going on about illegal coal mining," he continued. "The police stations and government building had been seized, too. "Because I had to stay in Donetsk, I went to the synagogue and explained my predicament, so the rabbi invited me to the communal seder. "There were roadblocks going up, but they didn't want to believe war was coming. "Usually at Pesach, we say, 'next year in Jerusalem', but I told them, 'let's hope, next year in Donetsk'. "Unfortunately, most of the Jews there have left."

|