|

PROFILE I survived Holocaust to fight for animal rights | |

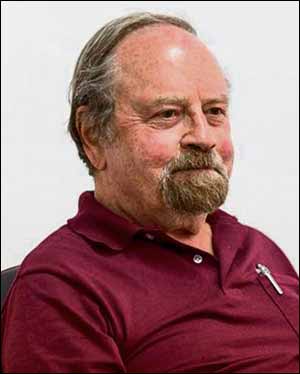

DR Alex Hershaft pauses for a moment to think about the question he must have been asked thousands of times.

The Holocaust survivor responds: “When I first saw animal parts in a slaughterhouse in 1972, I made the connection with the piles of Jewish bodies I saw during the Holocaust. “We have to be careful when it comes to any comparison, but, in a moral universe, there has to be compassion and consideration for every living being.” Now 82, Dr Hershaft, who is one of the world’s most prominent animal rights activists, survived the Warsaw Ghetto and many months in hiding during the Holocaust. Most of his family, along with 400,000 other ghetto inmates died from starvation, disease or in the Treblinka gas chamber. Dr Hershaft spoke to me while in London as part of his European speaking tour, co-ordinated by ProVeg, an international food awareness organisation, which included a talk at the capital’s Jewish Museum. He had a career as an environmental chemist and the time he spent campaigning for environmental causes were, he recalled “satisfying”. But, he said, “they didn’t answer the fundamental question of what were the lessons of the Holocaust”. And it was only when his work took him to a slaughterhouse that he found his true vocation. Dr Hershaft explained: “It was when I finally realised that there was a valid reason for my surviving the Holocaust and a valid way to repay my debt for surviving. “It was when I resolved to spend the rest of my life fighting all forms of oppression, starting with our oppression of animals raised for food.” It led to him becoming vegan and co-founding the Farm Animal Rights Movement. Today, he is a member of the advisory council of Jewish Veg in America and patron of the Jewish Vegetarian Society. Dr Hershaft, who now lives in Bethesda, Maryland, has endured a long and difficult journey to where he is today. He was born in 1934 into a non-practising Jewish family in Warsaw, to parents Sabina and Jozef. His mother was a mathematician, while his father was a chemist who researched the properties of heavy water at the University of Warsaw, alongside the famous Polish Jewish physicist Jozef Rotblat, who later worked on the Manhattan Project during the Second World War. The Hershafts did not live in a Jewish area but, when the Nazis arrived, they were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. “We actually moved into my grandparents’ apartment which I remember being nice,” Dr Hershaft recalled. “It was across the road from an infamous prison called Pawiak. “I remember the Nazis building walls around us and enclosing us in. “I was frightened because, even as a child, I would absorb what the adults were saying.” By late 1942, the Nazis began to liquidate the ghetto, sending inmates to their deaths in concentration camps. Salvation for the Hershaft family came in the form of a Russian maid who had lived with Dr Hershaft’s grandparents. As a non-Jew, she had a permit to go in and out of the ghetto. She eventually took Dr Hershaft out of the ghetto, receiving help from his aunt, the famous theatre actress Elzbieta Kowalewska, who helped hide escapees from the Warsaw Ghetto. He went into hiding, pretending to be non-Jewish while his mother, Sabina, who also passed as a gentile, would visit Warsaw and buy used clothing and bale to launder it and sell to villagers around the capital. But, in 1944, on one of her trips back, the Warsaw Uprising broke out and she could not return. Sabina ended up in Solingen, in Germany. The city was home to a camp for Italian prisoners of war, where she met an Italian pilot. They later married and headed to Poland, where Sabina and her son were reunited. But Jozef had died following internment in a German slave labour camp. “We moved to Italy, where I spent five years near Rome,” Dr Hershaft explained. “Later, my mother wanted us to move to America, but the American consulate decided she had communist sympathies and would not grant her a visa “This was in 1951, at the height of McCarthyism.” By now in his late teens, it was decided Dr Hershaft would go to America, while Sabina went to Israel, where she lived until her death in 1996. He went to read polymer chemistry at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, before gaining his PhD in organic chemistry in 1961 from Iowa State University, where he was employed by the Ames Laboratory of the Atomic Energy Commission. “It was a very bad time when I went to America and my mother went to Israel,” Dr Hershaft recalled. “I was a mamma’s boy.” But it was in the Jewish State that he first became involved in activism, having moved there in 1961 to teach X-ray crystallography at the Technion in Haifa. He staged a major demonstration in Tel Aviv, which led to the formation of the League for Abolition of Religious Coercion in Israel, a massive movement seeking to end repression of secular, Reform and Conservative Judaism, as well as mixed marriages, by entrenched Orthodox authorities. Dr Hershaft recalled: “There was a case of a Jewish man and an Arab woman who had fallen in love and had a baby, but the Israeli authorities took the baby away. “The mother tried to take the baby back and she was put in jail. “It really upset me, so we arranged demonstrations. “People wrote to tell me that I should set up an organisation.” Two years later, he turned over leadership to Uzzi Oman and his other Israeli deputies, as he returned to the America. It was in Israel that Dr Hershaft married Eugenie (nee Krystal), who had also been born in Poland and escaped with her family to Russia and Uzbekistan during the Holocaust. The couple, who divorced in 1979, had a child, Monica. Dr Hershaft turned vegetarian while living in Israel. “I kind of always had a problem with eating animals,” he said. “The concept of taking a beautiful being, hitting it over the head and cutting up the body into little pieces for people to shove into their faces seemed pretty gross. “It was easy to be vegetarian in Israel because there was not the same meat culture as there was in America. “The Israeli diet is not meat-centric. Once I was back in America, I was more closeted about my vegetarianism. “The general knowledge of eating animals and its products did not become widely known in America until people testified in front of the Senate on the consumption of animals.” And, although meat plays a large part in the Ashkenazi diet, Dr Hershaft believes Jews can easily adapt to a vegan diet. “We are no different to anyone else and, actually, the Torah is very kind to animals,” he said. After returning to America in 1963, he analysed naval operations for the Centre for Naval Analyses, before working in water pollution control and solid waste management. Dr Hershaft became involved in the vegetarianism movement in America after attending the World Vegetarian Congress in 1975. “There were people there from all over the world and from all different economic backgrounds,” he said. “It had an emotional impact on me, so I decided to set up the Vegetarian Information Service, which distributed information on the benefits of a vegetarian diet.” That later became the Farm Animal Rights Movement after Dr Hershaft had turned vegan and founded Action for Life, a national conference which centred on animal rights. Participants included the animal rights pioneers Peter Singer and Henry Spira, both of whom were Jewish. By that time, Dr Hershaft had quit his job at a systems engineering company to concentrate on a career in activism. “Animal rights’ activists started to ‘come out’ after reading Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation,” he explained. “Until then, they were frustrated that they did not have an outlet to exercise their views. “My theory is that we treat animal rights as a social justice cause. “With animal rights, it is not just about not eating animals. “Traditional advocacy does not truly work — you cannot just list the reasons not to eat animals to people and try to appeal to their emotions. “What you need to do is to change the whole system, as well as attitudes on the ground. “You need to support those who create a plant-based diet and, therefore, increase the demand. “In that instance, we have worked with food services and school and hospital cafeterias to encourage them to have more vegan items on their menus.” Over the years, animal rights activists have sometimes used violent methods when trying to draw attention to animal testing in various laboratories, both in the UK and America. Dr Hershaft continued: “There is never room for violence, but I will always condone liberating animals. “I feel that we have an obligation to all sentient, living beings. “When someone talks to me about ‘gay rights’, I do not think about the philosophy behind it, I think that it is my obligation not to discriminate against a gay person. “It is the same with animal rights. It is about how we should relate to all living beings.” Such is his devotion to the cause, he does not involve himself in personal relationships, as “they are a distraction”. He said: “I devote myself to the cause of animal rights and veganism.”

|