|

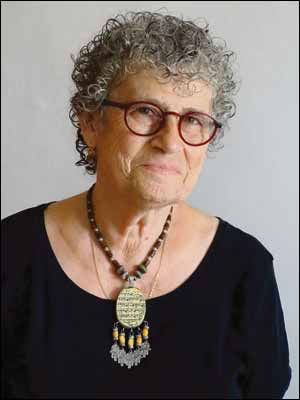

PROFILE Susan’s taste for archaeology led to history of haroset | |

But her mother told her it was not a nice job for a Jewish girl. Her mother might have been happier if she had known then that her daughter would end up taking on the more traditionally feminine role of food historian . . . and writing Haroset – A Taste of Jewish History (Toby Press). But before she became fascinated by the history of food in rabbinic literature, Susan did fulfil her dream of becoming an archaeologist. She told me: “It wasn’t till I was 35 and had five children that I decided I was no longer a nice Jewish girl and that I could go back to university and study archaeology.” But those days were far off when Susan was a pupil in Wallasey Hebrew Congregation’s cheder. She recalled: “My brother and I were horrible in cheder, but we enjoyed it.” When Susan was 11, her family moved to London. She said: “They decided that there were too few Jewish children and social activities left in Wallasey where people had moved during the war to escape the bombing but were then leaving. “If I wanted to go anywhere I had to cross the ferry to Liverpool. We used to get our kosher meat on the Mersey ferry.” The family moved to South Woodford. Susan explained: “It was not a very Jewish area. My father was a GP. All family doctors wanted to move to North West London. We didn’t have the right connections, so we went to the south east.” It was at Ilford cheder that Susan was inspired by Jewish studies teacher Rabbi Dr Irving Jacobs, who later became principal of Jews’ College. Susan studied English literature at Oxford, where she was studying when Jerusalem returned to Jewish hands during the 1967 Six-Day War. She recalled: “I thought, we ask three times a day to return to Jerusalem, now we can do it. It seemed the right thing to do.” But first Susan (nee Shannon) married Dr Michael Weingarten and had a baby. They made aliya in 1973. Michael, a professor of family medicine, was involved in setting up a new medical school in Safed. She told me: “I spent seven wonderful years in Safed and had five children.” The family then moved to Petach Tikvah from where Michael — who died last year — was commuting to teach at Tel Aviv University. As a family member of a university teacher, Susan was entitled to free tuition. She really loved studying classical archaeology and went on to write a doctorate on the subject. She was fortunate that the course’s compulsory field trips were on digs near her home. She said: “It was wonderful. I used to go off in the summer for a few weeks at a time. I loved working with a paintbrush on very delicate things or using a pickaxe to break things.” The septuagenarian said: “Now that I am more decrepit, I do my digging in the library. But I still regard myself as an archaeologist as well as historian.” During her university course, Susan discovered a seminar on the synagogue in Tel Aviv University’s department of Jewish studies. She thought if she were to dig up a synagogue she needed to know what the sources said. The course introduced her to the historical study of Talmudical sources which she found “exciting”. She was so excited that she decided to read the whole of the Talmud, taking university courses in Babylonian and Palestinian Aramaic. After her doctorate, Susan took a post-doctorate job at Tel Aviv University’s Jewish studies department. She recalled: “One day I was in a library reading a book called Women in Late Antiquity, which said that we know lots about food in late antiquity, but that we know almost nothing about how it was prepared. “The author had obviously never opened a Talmud in her life. In Masechet Shabbat there are endless details on how things are cooked. “When I saw that this woman had no idea about the whole lot of stuff in the Talmud about food preparation, I thought maybe no-one else had looked into it.” That became Susan’s principal area of research. “I go every year to the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, a multi-disciplinary conference for historians, anthropologists, sociologists and chefs,” she said. “I write a different paper every year on food in the Talmud. I ended up writing three papers on the history of haroset. My husband suggested I should make it into a book.” Haroset – A Taste of Jewish History details the history of charoset from the first possible reference in Matthew’s Gospel, through centuries of rabbinic literature to the present day.

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|