| Yad Vashem Special Focus | |

| Holocaust dilemmas facing teachers, mothers, doctors | |

NO matter how many times anyone visits Yad Vashem, they are left with the same numbing, cold feeling. The sense of shock is still the same.

Yet, the exhibits themselves are only a small part of the story. They are the result of painstaking research, worldwide trawls for material and the generosity of those who have donated memorabilia or dedicated parts of the Jerusalem Holocaust memorial in the names of murdered loved ones or in gratitude for their own survival. But behind the scenes, there is so much more. I have just returned from participating in a unique Jewish media seminar — four days of lectures and insights into Yad Vashem, a place I have visited many times and which I believed I know fairly well. I now realise how little aware I was of what it is all about and the message it aims to deliver, as well as what the Yad Vashem experts believe to be the true interpretation of the Holocaust — or in some cases, the misinterpretation. A surprising observation by one lecturer contradicted what I had always been taught . . . and what so many Israeli politicians and Jewish leaders over many decades have stressed. Israel, he insisted, was not born out of the ashes of the Holocaust. It would have happened anyway. Over the next three weeks, I will be featuring much of what I learned. Shulamit Imber is Yad Vashem’s pedagogical director at the International School for Holocaust Studies. She spoke on Holocaust remembrance in a world with no survivors, something which is becoming increasingly closer and a reality as the numbers of those who escaped the Nazis diminish daily. “In the world without Holocaust survivors we will have to use material which has meaning,” she said. “I don’t believe in holograms. I think what brought the commitment to survivors was meeting them. You see the face and the body language. “Use modern techniques, of course, but modern techniques that don’t trivialise the Holocaust. You have not to look for gimmicks. “What people took with them, objects etc, do more than holograms.” She added: “I’m very worried today that the Holocaust is becoming a symbol for evil without understanding what happened. “If people don’t learn about it, they won’t learn from it.” In Israel, Holocaust education begins far earlier than elsewhere because children are exposed to Yom Hashoah as a day of remembrance. Mrs Imber observed: “A historian teaches about the past. An educator gives history relevance. “We have to rescue the individual person from the pile of bodies to teach about it. We begin teaching the Holocaust before 1933.” Students, she said, must not be traumatised — the Holocaust was a traumatic event that contradicted education. Many students in Israel developed stomach pains before Yom Hashoah. Mrs Imber addressed some of the moral dilemmas facing those in camps or ghettos. She said she preferred to ask how, for instance, 400,000 survived, rather than how 100,000 died as the Nazis tried to starve and dehumanise them. What did mothers do when they could not feed their children? It was impossible to survive on the allocated 187 calories each day, so if a 10-year-old child smuggled food into the ghetto, was that considered stealing? Smuggling is stealing, said Mrs Imber, but in a mother’s diary it was described only as smuggling. “She said, in a world of chaos, smuggle a potato, but don’t steal a watch. We are not thieves.” Mrs Imber went further: “What do you do when a child is starving? Give a whole potato or save some for another day? Or a whole loaf of bread? “They were building alternative lives for their children so they didn’t become thieves.” A further dilemma for mothers, related in their diaries, was seeing their children stealing from each other. Doctors, too, faced dilemmas and decided to document what had happened because they feared the end of the Jewish world and wanted their voices to be heard. They worried that, for instance, if there were 100 sufferers of diabetes in a hospital with only enough smuggled insulin for three months, should they use it all, which would mean that all 100 died within a month? Or administer it to those with lesser severe diabetes who would survive longer than those with the worst symptoms? One judge suggested that by so doing the doctors would be practising Nazi medicine, while a rabbi said he was unable to provide an answer, since it would be asking him to play God. During the Holocaust, said Mrs Imber, the question was often bigger than the answer. Doctors consulted a committee on such dilemmas, but whatever either decided, people would still die. A further dilemma involved those caught up in the Holocaust asking: ‘Why did I survive and he didn’t?’ Mrs Imber said: “People went through moral dilemmas every day. They didn’t hide it. After the Holocaust they didn’t speak about it, but in the diaries they discussed it very honestly.” Yad Vashem is appealing to survivors for memorabilia. The appeal is limited to Israel, but those outside who can provide artefacts are sought, too. There is no accurate indication of how many survivors are still alive and Mrs Imber points out that they number survivors from 1935 Germany onwards. Over the next two weeks, I will include discussions on behind the scenes of Yad Vashem’s archives; Israel and the Holocaust; the art museum; behind the scenes of the artefacts’ collection; survivor testimony; Jews saving Jews during the Holocaust; the Jewish world and Holocaust remembrance and many other topics.

If you have a story or an issue you want us to cover, let us know - in complete confidence - by contacting newsdesk@jewishtelegraph.com, 0161-741 2631 or via Facebook / Twitter

|

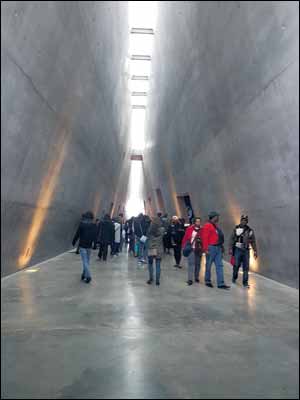

The corridors of Yad Vashem

The corridors of Yad Vashem